A Hierarchy Of Harms And Agency In Patriarchy Incarnate

It was good to receive an invitation from doctoral law student Saarrah Ray to speak at the Oxford University ‘Four College’ event, this time on 20 May 2022, when students from Christ Church, Corpus Christi, Oriel and University Colleges come together, this year to consider female genital mutilation (FGM).

It was good to receive an invitation from doctoral law student Saarrah Ray to speak at the Oxford University ‘Four College’ event, this time on 20 May 2022, when students from Christ Church, Corpus Christi, Oriel and University Colleges come together, this year to consider female genital mutilation (FGM).

A number of excellent speakers made presentations, and I too contributed, offering my developing perspective on the issues around the economics and politics of patriarchy incarnate and FGM.

Particularly, I am becoming convinced that this patriarchy incarnate arises at a range of levels of severity from the ‘trivial’ to the undeniably atrocious – all of them significant because these ‘levels’ feed into and reinforce each other. Importantly, consideration of patriarchy incarnate invokes whenever it occurs this question: ‘Where (and who) is the agency in this phenomenon?‘.

The answer to this question is generally that the agents of patriarchy incarnate, however it materialises, are men seeking wealth and influence; and the stark realities which lie behind that bald statement are cause for alarm to many of us.

The paper in which I explored this theme follows below. May I suggest that you check out the links here to the various aspects of this topic? You may find them alarming.

A Hierarchy Of Harms And Agency In Patriarchy Incarnate

Is the focus of white western activists on female genital mutilation (FGM) hypocritical? Quite a few commentators say so, but I am on the whole unconvinced.

The claim is that we westerners criticise FGM but are less concerned about female genital cosmetic surgery (FGCS). ‘How is that different from what happens in some traditional communities?’, is a question asked quite frequently.

Amongst other matters, this question makes the assumption that the westerners trying to end FGM are the same people who favour FGCS. Not only do I suspect this is untrue, but it also seems reasonable to assume that most women who seek FGCS are not even aware in any focused way of what FGM actually is.

And those EndFGM activists I have discussed this with are generally concerned about the same issues – consent, age, vulnerability, etc – in regard to FGCS as they are to FGM.

This, however, is but one part of the ‘traditional’ vs ‘western’ perspective which we need to consider.

I have previously developed my view that FGM is one very significant example of Patriarchy Incarnate – the imposition of (some) men’s will on the bodies of women and girls.

I will here try to take this concept forward, to consider the ways in which patriarchy incarnate impinges on modern western lives, as it does on the lives of people in traditional communities.

So what is Patriarchy Incarnate?

In previous work I have defined patriarchy incarnate as

‘the literal imposition of some men’s will on women’s bodies.’

Initially I saw this term as applying only to female genital mutilation, but I have now begun to understand how the term can also be applied to other aspects of patriarchal imposition, both physical and psychological. In real life little distinguishes soma and psyche; harm to either is harm to both, especially when the harm is inflicted knowingly by fellow human beings.

It’s always helpful in considering patriarchy to refer to the Costa Rican feminist jurist Alda Facio Montejo, who reminds us that

…[i]n any given Patriarchy all men will not enjoy the same privileges or have the same power. Indeed, the experience of domination of men over women historically served for some men to extend that domination over other groups of men, installing a hierarchy among men that is more or less the same in every culture or region today. The male at the top of the patriarchal hierarchy has great economic power; is an adult and almost always able-bodied; possesses a well-defined, masculine gender identity and a well-defined heterosexual identity….

The details of the domination and violence vary across different places and times, but the key feature is that women are controlled by powerful men. Sometimes the control is direct, sometimes it is via others (women or men) who do the bidding of the dominant males; but always it is to the advantage of these controlling dominators.

Importantly, one factor emphasised above is that the advantage for powerful men is economic as well as personal. All patriarchal systems are fundamentally about inequalities of benefit and opportunity; and patriarchy incarnate moves beyond that to acknowledging the real harm to the bodies and minds of women and girls which can be an element of that domination.

There is within the general concept of patriarchy incarnate what might be termed a ‘hierarchy of harm’, from seemingly inconsequential and fleeting impacts on women and girls, to the most horrendously direct and irreversible damage.

I will however argue that this continuum of harmful impact exists organically as a whole; and I would also suggest that what distinguishes human male domination (or sex-determined ‘leadership’) behaviour from that of other mammals is that humans alone are able to see it for what it is, and – to whatever extent in different contexts – challenge it.

Harmful practices

The act of female genital mutilation is quintessentially patriarchy incarnate. It is a harmful, sometimes fatal, incursion, directly or indirectly by fathers and maybe other male relatives, which damages female genitalia, with the time-honoured intent of increasing the market value of girls as commodities to be sold to other men. That the actual procedures are often undertaken by women is immaterial to the underlying purpose of the act, which has already been inflicted on those, (grand)mothers, aunts and midwives, now imposing it anew on the next generation.

FGM thus stands as a hugely significant example of patriarchy incarnate; but it is by no means the only behaviour which earns this categorisation. Nor can it be said that only traditional communities and societies demonstrate harmful patriarchal practices.

Nonetheless, it is helpful to consider which other ‘harmful traditional practices’ comprise patriarchy incarnate. Amongst these are breast binding, forced fattening, purdah and much else. A considerably more extensive list of these ‘traditions’ can be found here.

As is so often the case, however, there have quite recently been moves to critique the term ‘harmful traditional practices’ (HTP) because of the claimed dislike of it in some communities, and the implication that this term suggests ‘only’ traditional communities are engaged in such activities. It is suggested too that the term ‘HTP’ implies a colonial, Christian perspective that is unacceptable to Muslim culture and women, who are ‘often’ treated as having little say in their lives.

For these reasons the recommended term is often ‘Violence Against Women and Girls’ (VAWG), not HTP. Whilst there is substance to this critique, however, I do not see the term VAWG as encompassing all that is required regarding the nature of such harm. I would for preference use the term ‘Patriarchy Incarnate’, at least when it comes to the formulation of perceptions and paradigms through which to seek an understanding of these gendered harms.

These are some reasons for such a preference:

- Whilst it is always constructive, sensible (and polite) to use terms acceptable to those concerned when actually in their communities, it is important in more general discussion to bring a focus to the origins of such practices – many of them originate way back in history, and are linked to a plethora of traditional beliefs and ways of life.

- Most contemporary versions of VAWG are connected with the ‘traditional’ ones in some way; but they are indeed different.

- So there are occasions when VAWG is the most helpful way to refer to harmful behaviours, just as there are other occasions when HTP is more useful.

- Neither HTP nor VAWG brings a focus to the perpetrators of the violence – who by a large majority are male.

- Further, neither HTP nor VAWG reflects the critical underlying truth that such violence is almost always connected with some men’s economic advantage and amplification of power.

Hierarchies of harm

FGM is one of the most grim examples of patriarchal power inflicted on the bodies of women and girls. Of course not all men, even in traditionally practising communities, want to see their daughters ‘cut’, and more than most mothers do – many stay away when the ‘procedure’ is inflicted, and often the whole process is conducted after the consumption of ‘celebratory’ alcoholic drinks. Nonetheless, the harm of FGM is both physical and psychological (possibly for some perpetrators, as well as for their victims?), and can be life-long, even invading the next generation, put at risk by the damage to their mothers.

As we have noted, however, FGM is not the ‘only’ sort of serious harm experienced via patriarchy incarnate. We have seen that other traditional harms have also blighted the lives of women and girls.

But some harmful practices are easily identified also in contemporary ‘modern’ societies, and they can be as dangerous and destroying of women and girls now, as are the more historical ones. A prime example of this is child marriage – still permitted in some USA states for children as young as twelve (20 states have not set any age at all), whilst only Delaware, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island have set the minimum age at 18 and eliminated all exceptions. In effect, most parts of the USA permit what would otherwise be seen as statutory (juvenile) rape.

Campaigns to stop child marriage in India have been active for a century, but still they rage also in the nation seen as the leader of the Western world; and in England and Wales the minimum age for marriage has been established as 18 only this year, in 2022. Even now, marriage at 16 is permitted with parental permission in Northern Ireland, and actually without that guidance at all in Scotland.

It is striking therefore that in many African countries, although a few still permit marriage for girls at 15, legislation in most nations prescribes 18 as the normal minimum age for marriage; and in some locations it is even higher than that: little scope here for any claims to ‘better protections’ in the global north.

Also of note is that some countries set a higher age for marriage by boys / men than they do for girls / women. It seems that girls – even though their young bodies will be bearing any subsequent children – are deemed to require less protection than boys. This is also significant in respect of gendered power imbalance, especially as more often than not young girls are married to much older men. Equality Now offers this observation:

Why is child marriage a feminist issue?

Child marriage affects girls at far greater rates than boys; 720 million women and girls alive today were married before age 18, compared to 156 million men and boys.

Because the vast majority of child marriages are younger girls to older men, there is an inherent imbalance of power in these relationships, which is often linked to domestic violence. In addition to the physical danger this presents to women and girls, violence can also have lasting psychological implications on girls’ and women’s mental health.

According to the International Council of Research On Women (ICRW), women with low levels of education and married adolescents between the ages of 15-19 years old are at a higher risk of domestic violence than older and more educated women. Globally, girls who marry before age 18 are 50 percent more likely to face physical or sexual violence from a partner throughout the course of their life.

These disturbing facts are not however exceptional as ways in which the bodies and minds of women and girls in the ‘developed’ world are subject to the will of powerful men.

Consider, for example, ‘purity balls’, whereby quasi-bridally garbed girls – often young teenagers – are taken by their fathers to formal events, a dinner-dance, where the father pledges to ‘protect’ his daughter until marriage, and she in turn pledges to keep her body ‘pure’ until that time. The underlying values of that event are clear, but are deeply compromised by the likelihood that the majority of these daughters will break their pledge, doubtless to the distress and long-term psychological damage such ‘failure’ will bring.

Purity balls are a phenomenon of only the past few decades, but perhaps there are parallels here with the First Communion celebrations of some Christian denominations, which also focus more on girls and their ‘purity’ than on that of their brothers. Certainly, the price which was until paid by these girls if they became pregnant before marriage was (sometimes still is?) vastly greater than that of the men or boys who got them into ‘trouble’. If evidence of this perspective were needed, ‘churching’ provides evidence that childbearing and birth were seen as a ‘sin’, to be washed away by a priest in a church some weeks after delivery. The most definitive versions of this view were probably held in Ireland by Roman Catholics, but the tradition goes back a long way and is still recognised as a ‘thanksgiving’ in some UK Anglican churches. Similar ceremonies are / were also conducted in other parts of the Judeo-Christian world.

Here then we have women being cleansed of their bodily ‘impurity’ by men authorised to do so. However much this practice is now consigned to history, how is it different in its fundamental philosophy from the current attempts by very powerful men (along as ever with some supporting women) in America who wish prevent pregnant women from obtaining terminations, even in the most dire circumstances?

Perhaps the alarming historical analysis by Randall Balmer of the religious right in the USA goes some way to answering this question.

We have seen that patriarchy incarnate reaches into the minds and bodies of women in many parts of the globe even now. The complex and creative bodies of women are seen as impure, and / or in need of control, by men with authority in many locations across the world. In some South Asian countries the practice of purdah and menstrual exclusion (often in grim conditions) continue; in other countries – including increasingly in some USA states and Hungary, even perhaps some parts of Australia, along with nations like Afghanistan and Iran and, perhaps, Japan – women are seen from one perspective primarily as ‘baby machines’. And to that we can add the increasing insistence on full bodily coverings for women in parts of the Middle East as well as South Central Asia.

These practices, inculcating shame and fear in the minds of young girls and women, and distain (or worse) in boys and men, have existed for centuries. There is however one further way in which patriarchy becomes incarnate: when the patriarchy uses the bodies of girls and women as a whole for economic or military gain. In other words, to enhance the power of some men. This is what happens when girls and women – for the large majority of victims are female – are trafficked, or raped in conflict, when (mostly) female bodies are used as a tool in war, thereby ‘punishing’ their husbands and male relatives, violating their place in their community and impregnating them to reduce the cultural or historic identity of that group.

It is even a tragic truth that sometimes in war mothers arrange for their daughters to have FGM to ‘protect’ them from rape. This report from 28 Too Many tells us how damaging such a strategy can be:

…. research shows that incidences of rape increases in emergency situations and violent forced sex can be especially dangerous for women who have had FGM. When women has had Type III FGM (infibulation), forced penetrative sex can cause severe physical trauma, haemorrhage, shock and in some cases death. This risk is much worse as health support may be limited or non-existent in emergencies. Case studies recorded by 28 Too Many have illustrated the exaggerated complications associated with sexual violence against women and girls with FGM. In refugee camps in Sudan girls as young as ten were found pregnant as a result of rape, having undergone FGM as young children, almost dying in childbirth. There are obviously specific physical and psychological complications associated with pregnancy and childbirth in young girls, particularly for those who have undergone FGM. With occurrences of rape increasing during crisis situations, including the rape of young girls, there will be a corresponding increase in young mothers and childbirth complications associated with FGM. In further case studies from Nigeria, vulnerable and displaced women and girls reported being forced to have FGM to prepare them for prostitution which was their only means of survival.

All the practices discussed here continue to varying extents to the present day in different parts of the world. These intentional acts instigated by state or other powerful agencies are patently patriarchal assaults on the bodies and souls of women. They lie at the apex of the hierarchy of patriarchal harm.

From trivia to terror

It might seem trivial after an examination of the cruelties above even to mention day-to-day ‘sexist’ behaviour, but these may in modern societies be the baseline which dulls our horror at the practices we read about elsewhere. The historian Lucy Worsley declares that ‘Women still face the prejudices that led to witch-hunts.’ Worsley’s focus is on people – most of them 16th and 17th century Scottish women – who ‘lacked power in the past’. Still, we are told, ‘Anyone who has ever been put down as a ‘difficult’ woman bears a distant echo of the past.’

The witch-burning of the past has gone from modern societies, but this sort of behaviour continues, eg, in nations which still include the stoning of (mostly) women for adultery in their penal codes. Nor, as declarations such as the Seven Mountains Mandate make clear, are the attitudes and beliefs which underly some of this behaviour, held by some international political leaders including Scott Morrison (Australia) and Donald Trump (USA), particularly hidden from view.

The ways in which Worsley’s ‘distant echo’ resounds are innumerable, but examples in modern Western democracies might include sexual comments, touching, being ‘unseen’, inequitable treatment at work, a greater domestic burden, and much else. In authoritarian ‘democracies’ or the developing world the inequalities are often much more striking: denial of child-bearing choices, ineligibility to inherit or own land, inequality before the law, etc – all in addition to the indignities experienced by women in the ‘developed’ world.

The evidence for a hierarchy of harms is multitude. What is dismissed by the perpetrator as ‘a bit of fun’ – a brief touch, a smirked suggestion, a misplaced comment – is the first permissive foray in what, perhaps for other men, becomes a grope or worse; and that in turn enables some men to believe they have the ‘right’ to tell ‘their’ women what they may or may not do, even in regard to the most intimate of matters, such as control of their own fertility.

From here it is perhaps not a reach too far to believe that the use of the female body as a commodity is acceptable – whether that be as a trafficked human being, a ‘pure’ bride as merchandise, or even as a humiliated rape victim, to show superiority of the aggressor in conflict situations and to weaken ‘cultural’ ties in the next generation of babies.

What starts as an off-colour ‘joke’ can become, from the perspective of patriarchy incarnate, a belief that it is legitimate for men to control women’s fertility or even, at the extreme, the use of female bodies for the oppression of others, male and female alike.

This is the hierarchy of harm which patriarchy unchallenged can impose to varying degrees on the soma and psyche of female human beings, and in fact on all less powerful people. Patriarchy is not of itself about sex or gender, it is about the accrual of wealth and influence as a means to dominate others; and patriarchy incarnate does that very well.

So is FGM the same as FGCS?

And so we return to the question we asked as this discussion began: Is it hypocritical for westerners to seek the abolition of female genital mutilation (FGM) in developing nations, whilst female genital cosmetic surgery (FGCS) is accepted in the developed world?

To answer this question we need to understand who (which women and girls) seek this surgery, and we need also to understand the concerns which lead them to do so. I consider both these aspects of FGCS in my chapter in a 2019 women’s health book.

Most girls and women who seek FGCS are vulnerable because they believe – and may have been told by people close to them – that their bodies need to be ‘improved’. There are obvious parallels here with the rationales for FGM, but it is very unlikely that the women seeking genital cosmetic surgery will be aware of these parallels.

And on the other hand, those western women who oppose FGM by ‘traditional’ methods are also usually opposed to the medicalisation of this practice. Nor, in general, are they promoters of FGCS. We tend to hold that, physical (or just occasionally psychiatric) medical necessities apart, our bodies are best left as they are.

But there is a bigger matter which must be considered in all this: Both FGM and FGCS arise from patriarchal perspectives on the human female body. Both, in fact, are features of patriarchy incarnate.

Words and questions for a more equitable world

We began with an examination of FGM as patriarchy incarnate. I have then sought to demonstrate that patriarchy is much wider in its impact on female bodies than ‘only’ FGM.

Most campaigners against FGM and violence against women and girls (VAWG) will continue to use this sort of vocabulary as they go about their day-to-day work. These sorts of terms make sense to most people and are important because they are respectful of the language employed ‘on the ground’.

In any wider analysis of violence against women and girls, however, it is critical to move beyond descriptions of impact, to consider carefully who are the agents, the people who impose these harms? In a large majority of cases, these agents are powerful men, men who inflict actual damage to the bodies and minds of women in order to enhance male wealth and power.

Further, many ‘ordinary, relatively powerless, men are in reality victims of this patriarchal violence, even when they also themselves impose it on ‘their’ womenfolk. Intimate violence is often inflicted by men, perhaps of lower status, or unsure of themselves wherever they stand in the social hierarchy, who know of few other ways to demonstrate any aegis or supposed control over their situation.

Put another way, patriarchal behaviours at a high, powerful level of influence may also trigger harm to women and girls by men who have learnt from boyhood that they have few other ways to make their presence felt. Whilst this excuses nothing, men and boys can also thereby become the victims of patriarchy incarnate.

To face up to the violence which, to whatever degree, most women and girls (and some men and boys) experience throughout their lives it is essential that, as well as acknowledging the harm that is done, we name the agency of these acts.

That agency, whether directly or indirectly, is male, powerful, and wealthy; and such men are unlikely, unbid, to be committed partners in the eradication of FGM or other cruelties inflicted on women.

Laws may be agreed, medics may create protocols, sanctimonious demands may be made, but we already know these alone rarely achieve great success. That is where consideration of the hierarchy of harms from patriarchy incarnate may serve a purpose. The term patriarchy incarnate demands an answer to the question ‘who is responsible for this harm?’ And it also demands that we ask who is benefitting from this harm, in what ways?

These questions are why I, as an academic activist against FGM, child marriage and VAWG in general, believe I can make my best contribution by studying the economic advantage and political power play of wealthy men who would prefer we didn’t ask any questions. The more we know about for whom, and why, patriarchy incarnate is beneficial, the closer, I hope, we shall be to supporting the women and girls we want to protect and nurture.

Many workers strive ceaselessly on the front line of VAWG, but some are in the back room trying to unravel the mystery of why harm to women and girls is so ubiquitous.

A hard look at the agency implied in the term patriarchy incarnate is a part of that unravelling endeavour.

~ ~ ~

Saarrah Ray, DPhil Law candidate, Christ Church, University of Oxford, writes:

I am very grateful to have received the Four Colleges Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Fund which sponsored the Four College Rose Against Female Genital Mutilation Colloquium that I had the privilege to organise on 20th May 2022. The colleges in the title refers to Christ Church, Oriel College, University College and Corpus Christi College. This colloquium was born out of my doctoral research and feminist activism against female genital mutilation (FGM). In the quest to dismantle the silence around the hidden crime of FGM, I wanted to raise awareness about FGM amongst my peers at the University of Oxford in a way that the campaign against FGM would become a part of college culture.

I invited students to demonstrate collegial solidarity against FGM in the form of creating art which became The Four College Rose, 2022. Art is a brilliant way to bring people together; to challenge inequalities, to impart knowledge and to reclaim what has been misunderstood or ignored. I suggested that students draw roses because the rose is a universal representation of female genitalia, therefore, it is an important symbol in the campaign to end FGM. Throughout western literary history the rose was treated as fragile yet dangerous, tempting but at the same time disgusting and decaying. Artists and activists against FGM have retrieved the rose, now the rose is a symbol of female empowerment. Whilst students created their beautiful roses, they were engaged by the dialogues between expert guest speakers on FGM through the lenses of: feminism, politics, law, economics, sociology, art, fiction and obstetric healthcare.

The students were fascinated by the way in which each guest speaker approached FGM as form of violence against women and girls within their academic disciplines. The students felt inspired to know more about this harmful practice and they wanted to learn how they can get involved in the campaign to end FGM. The Four College Rose is the start of the campaign to end FGM in Christ Church. The Four College Rose is expected to be displayed in Christ Church on every 6th of February which is International Day of Zero Tolerance for FGM. I hope this is a start of a new tradition in College, one that is feminist and demonstrates support for women’s rights, unequivocally.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Read more about Patriarchy, FGM and Economics

and Child, Early and Forced Marriage (CEFM)

Your Comments on this topic are welcome.

Please post them in the Reply box which follows these announcements…..

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

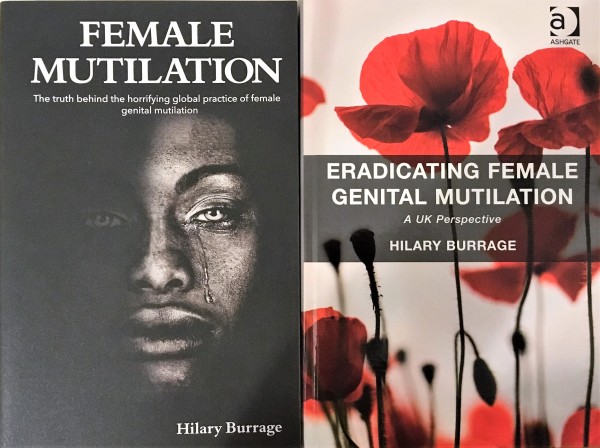

Books by Hilary Burrage on female genital mutilation

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6684-2740

Hilary has published widely and has contributed two chapters to Routledge International Handbooks:

Female Genital Mutilation and Genital Surgeries: Chapter 33,

in Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health (2019),

eds Jane M. Ussher, Joan C. Chrisler, Janette Perz

and

FGM Studies: Economics, Public Health, and Societal Well-Being: Chapter 12,

in The Routledge International Handbook on Harmful Cultural Practices (2023),

eds Maria Jaschok, U. H. Ruhina Jesmin, Tobe Levin von Gleichen, Comfort Momoh

~ ~ ~

PLEASE NOTE:

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, which has a primary focus on FGM, is clear that in formal discourse any term other than ‘mutilation’ concedes damagingly to the cultural relativists. ‘FGM’ is therefore the term I use here – though the terms employed may of necessity vary in informal discussion with those who by tradition use alternative vocabulary. See the Feminist Statement on the Naming and Abolition of Female Genital Mutilation, The Bamako Declaration: Female Genital Mutilation Terminology and the debate about Anthr/Apologists on this website.

~ ~ ~

This article concerns approaches to the eradication specifically of FGM. I am also categorically opposed to MGM, but that is not the focus of this particular piece, except if in any specifics as discussed above.

Anyone wishing to offer additional comment on more general considerations around male infant and juvenile genital mutilation is asked please to do so via these relevant dedicated threads.

Discussion of the general issues re M/FGM will not be published unless they are posted on these dedicated pages. Thanks.

This is a really thought provoking article – thanks! Here are a couple of my thoughts:

As someone relatively near the frontline on.the battle against VAWG (commissioner and strategist), I can see that we’ve focussed, for a long time, on victims and survivors. There are logical reasons for this, including – women being harmed need immediate help and we’ve limited resources, we can rarely successfully prosecute without a willing victim who is supported enough to make a complaint, supporting mum is usually the best way to support the children, work with perpetrators is often ineffective….. But this has left us frequently ignoring who’s responsible for the abuse and why they do it. So I like Patriarchy Incarnate – it reminds us of the perpetrators/s and puts their behaviour in context.

Police and other Community Safety Practitioners and commissioners have tended, in recent years, to reduce their focus upon the gendered nature of VAWG and many now see intimate partner and family violence as fairly gender neutral, with services needed by all. It’s good that male victims are getting a better deal, but it’s important to recognise the unbalanced nature of this type of abuse and frequent reference to the patriarchy will help us with this!

In the last few years, society has tended to replace consideration of the protected characteristic of sex with a focus upon gender. However, reading the above list of the harms done to women it is strikingly obvious that most of them are clearly directed at sexed bodies. Gender and gender identity are helpful concepts, in many contexts, but it’s very clear from the above that we must not forget about sex and how having a female body is the biggest risk factor for being a victim of most of the harms listed,

A shocking read.

The fact it is, on the one hand, about the taboo subject, female genitalia and on the other “entitled men” and their power and privilege, I presume makes fighting to stop FGM and other interlinking practices phenomenally difficult from the word go.

The age at which it is legal for girls to be married in some states in America in comparison to Africa was a shock too.

Apparently America is still in the dark ages.

I feel I’ve been naive and complacent.

Just a couple of small points. There are cases – due to a virulent cancer, of the removal of all or many of the reproductive organs (even some of the vaginal wall). The woman after many, many months of recovery will be scheduled for FGS to reattach areas that are possible to attach (complications with vaginal prolapse as an example). This cause of this type of cancer is often unknown, though speculated to be caused by an STD. Gardasil is a favorite vaccine for pubescent girls these days now (yet data is inconclusive but accepted).

FGS happens cosmetically in this case but anyone can understand that it’s only reasonable to be ‘corrected’. Not about striving for a prettier or slimmer vagina by any means.

[Hilary says: May I respond here to clarify? I am very clear that female genital clinical surgery – ie surgery conducted for real, medical reasons, whether cancer or congenital / obstruction etc – is just that: an (often essential) procedure to remedy illness or disablement.

My comments here relate only to female genital cosmetic surgery – ie surgery which, as I indicate in the post, women and girls actively seek as an option to ‘improve’ (in their opinion) the look or anticipated feeling of their anatomy.]

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Separately, just one other point – if we are to wholly accept ‘patriarchy incarnate’ as a term to describe the-world-as-it-is we must also say ‘women’s-complicity-in-that-world-as-it-is’ must be an important focus area to pour our energies, figuring out how that complicity can be broken.

What alternatives are available for not going along with the man, so to speak. There is no Greek island where women can go and create their own society, as described in antiquity literature.

There are still benefits for keeping quiet. Unless there is a equal pay as an example, it is not surprising that even the current generation of women are choosing to be homemakers, even the ones with university degrees if their husbands earn enough money (this is total-privilege example). But the fact remains this is a conundrum because as we know in the nuclear family, even to this day, the man has final say in many traditional households. The women may not want to admit it but something as simple of wanting to paint their kitchen cabinets has to be negotiated as he may not like the smell when he gets home from work. This is a petty example but equality is a long way away for women who live in traditional family arrangements.

[Hilary again: Thank you, and yes. I totally agree – and would add only that in my view there are also many men, perhaps the sort you describe here too?, who are likewise ‘victims’ of patriarchy incarnate; in common with most women, they have not much choice about how they conduct their daily lives – and that small degree of choice they do have can of course include trying to exert (and feel) power over the women in their lives. I am under no illusion that overcoming the patriarchy is a challenging, often almost impossible, task for individual ‘ordinary’ people, women or men; the best we can do in all probability is be aware of this powerful force and take any opportunities which arise to conduct our lives – and our children’s lives – without it if and when we can?]

Thanks Hilary- very detailed and thoughtful analysis of a huge problem

Really interesting, thanks Hilary.

We are well overdue a catch up too!

Thank you Gill; and I hope we can have that catch up soon 🙂