What Is Female Genital Mutilation? An Introduction To The Issues, And Suggested Reading

This briefing derives from my lecture (1 April 2016) on Female Genital Mutilation, to post-graduate students at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The notes will be updated occasionally, and will I hope serve as an introduction to most of the issues arising in the eradication of FGM, in both low-resource and more structured settings. Readers are welcome to make use of this blog, with the proviso only that my copyright and my two books on FGM are formally acknowledged:

This briefing derives from my lecture (1 April 2016) on Female Genital Mutilation, to post-graduate students at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine. The notes will be updated occasionally, and will I hope serve as an introduction to most of the issues arising in the eradication of FGM, in both low-resource and more structured settings. Readers are welcome to make use of this blog, with the proviso only that my copyright and my two books on FGM are formally acknowledged:

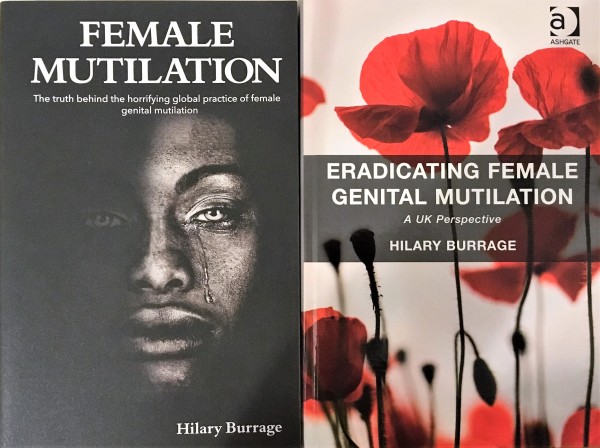

* Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation: A UK Perspective (Hilary Burrage, Ashgate / Routledge 2015). Contents and reviews here.

* FEMALE MUTILATION: The truth behind the horrifying global practice of female genital mutilation (Hilary Burrage, New Holland Publishers 2016). Contents and reviews here.

SUMMARY OF CONTENT

WHAT IS FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION, HOW IS IT CLASSIFIED, AND WHO DOES IT?

- Harmful traditional practices (HTPs)

- FGM: Who does the ‘cutting’? (Medicalization of FGM)

THE CONSEQUENCES OF FGM

- No health benefits, only harm

- Immediate complications

- Long-term consequences

- Obstetric fistula

SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF FGM

RATIONALES (‘REASONS’) FOR THE PRACTICE OF FGM

PREVALENCE AND DATA-COLLECTION (CHALLENGES)

LEGAL STATUS OF FGM.

TERMINOLOGY

FGM AND MALE ‘CIRCUMCISION’

CLINICAL APPROACHES AND TREATMENT

- General clinical care considerations

- Remediation

ERADICATION

- General issues / background

- Legal and Protection

- Campaigning / community

- Men (and community campaigning / impact)

- Education

- Alternative Rites of Passage (ARPs)

- Health

- Readiness for change

- Multi-agency or Inter-disciplinary?

- Speedy eradication is imperative

CURRENT PROGRESS IS INSUFFICIENT TO KEEP UP WITH INCREASING POPULATION GROWTH.

IF TRENDS CONTINUE, THE NUMBER OF GIRLS AND WOMEN UNDERGOING FGM/C WILL RISE SIGNIFICANTLY OVER THE NEXT 15 YEARS.

*Please be aware that discussion of FGM and other child abuse is difficult for some people, and that occasionally it can cause distress or trigger flashbacks.

This post was lightly updated in regard to reading / references on 25 March 2017.

* * *

WHAT IS FEMALE GENITAL MUTILATION, HOW IS IT CLASSIFIED, AND WHO DOES IT?

For an introduction to what female genital mutilation (FGM) entails please watch this video, by Comfort Momoh, Consultant Midwife at St Thomas’s Hospital, London:

- The facts you should know about female genital mutilation (FGM) (The Guardian, Feb. 2016)

Also essential for a global overview are these brief WHO and UNFPA reports, which offer a general guide to the facts of FGM and confirms that over 200 million women and girls currently alive have experienced FGM:

- Female Genital Mutilation (WHO Factsheet, updated Feb, 2016)

- Female genital mutilation (FGM) frequently asked questions (UNFPA Dec 2015)

The generally accepted World Health Organisation classifications for FGM are:

- Type I— Partial or total removal of the clitoris and/or the prepuce (clitoridectomy). When it is important to distinguish between the major variations of Type I mutilation, the following subdivisions are proposed:

- Type Ia, removal of the clitoral hood or prepuce only;

- Type Ib, removal of the clitoris with the prepuce.

- Type II— Partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora, with or without excision of the labia majora (excision). When it is important to distinguish between the major variations that have been documented, the following subdivisions are proposed:

- Type IIa, removal of the labia minora only;

- Type IIb, partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora;

- Type IIc, partial or total removal of the clitoris, the labia minora and the labia majora.

- Type III— Narrowing of the vaginal orifice with creation of a covering seal by cutting and appositioning (joining up) the labia minora and/or the labia majora, with or without excision of the clitoris (infibulation). When it is important to distinguish between variations in infibulations, the following subdivisions are proposed:

- Type IIIa, removal and apposition of the labia minora;

- Type IIIb, removal and apposition of the labia majora.

- Type IV— All other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example: pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization.

In some communities FGM of one sort or another is inflicted in private, perhaps even on young babies. In other communities it is conducted with ostentatious (and expensive) ceremony on pre-pubescent or teenage girls, or even, for the first time, on primigravidas just before they give birth.

In the case of Type 3 / infibulation the FGM may also be repeated after each pregnancy.

Harmful traditional practices (HTPs)

It is important to note that FGM is not the sole source of danger for (and control of) girls and women – and sometimes of boys and subordinate men too. Amongst the harmful traditional practices which have come to light (and are rarely perceived as human rights abuses in their normal contexts) are

- Albino abuse

- Beading (culturally sanctioned paedophilia) – and ‘kneading’ abortion of any pregnancies

- Breast ironing

- Domestic violence

- Dowry-related violence

- Dry sex (dangerous and painful for both sexes)

- Ebinyo (teeth pulling) – four times as prevalent in girls as in boys

- Forced and child ‘marriages’

- ‘Honour’ stoning and killing

- Hyena sex ritual (‘cleansing’ of a widow by licensed rape)

- Leblouh / gavage (forced fattening)

- Maltreatment of widows (eg widow ‘cleansing’ as above) and wife/widow inheritance

- Okukyalira ensiko (labia elongation)

- Sexual assault

- Sexual harassment

- Sex trafficking of women and girls

- Son preference and female feticide

- Twin infant killing and live burial of infants

- Witchcraft allegations and ‘spirit child’ allegations

See eg

- Fact Sheet No. 23, Harmful Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children (United Nations, Office of the High Commissioner Human Rights, ?1994)

Quote: Most women in developing countries are unaware of their basic human rights. It is this state of ignorance which ensures their acceptance-and, consequently, the perpetuation of harmful traditional practices affecting their well-being and that of their children. Even when women acquire a degree of economic and political awareness, they often feel powerless to bring about the change necessary to eliminate gender inequality……. It is essential to improve communication between men and women on issues of sexuality and reproductive health, and the understanding of their joint responsibilities, so that men and women are equal partners in public and private life.

(For the situation 20 years later, in 2016, see: Strong global support for gender equality, especially among women.)

- Harmful traditional practices in diaspora communities (Brown, 2014)

- Safeguarding African Children Series (AFRUCA, various dates)

FGM: Who does the ‘cutting’? (Medicalization of FGM)

Historically, FGM is undertaken by a traditional midwife or other senior woman within the community (often the grandmother or an aunt; and occasionally a man with similar authority). More recently however the ‘procedure’ may have been delivered by a clinically trained operator, perhaps a nurse, pharmacist, dentist or doctor. In most cases, whether the operator is traditional or clinical, a fee is paid – and in some instances the FGM may even be part of a ‘medical package’ following the delivery of the infant who is to be mutilated.

Traditionally FGM may have been (and in some communities still is) a very public ceremony involving many girls (sometimes boys also ‘due’ for circumcision) but now medically trained practitioners may set up temporary ‘clinics’ at the appointed time. In either case the event is lucrative for the operators, and the parents of girls undergoing the mutilation may feel reassured that the risks have been removed. (In fact, although local anaesthetic, sterile equipment and antibiotics be used, it seems that clinically trained operators cut and excise more ‘thoroughly’.)

The WHO, UNFPA and many other international, legal and medical bodies all emphasise that any ‘type’ of FGM, however delivered, is contrary both to legislations almost everywhere, and to globally recognised medical ethics. All FGM is harmful.

These UNFPA and WHO documents, which cover many aspects of tackling FGM, specifically consider ways in which midwives and other health-care providers can work towards the ending of medicalization:

- TOOLKIT: Midwives committed to the abandonment of FGM – ENGAGING MIDWIVES in the Global Campaign to End Female Genital Mutilation (UNFPA, ?2015)

Nonetheless, the medicalization of FGM is increasing in some parts of the world, to some extent in places such as Kenya, but especially in the Middle East and South East Asia:

- Medicalization of female genital mutilation/cutting (African Journal of Urology, 2013)

THE CONSEQUENCES OF FGM

FGM is a highly dangerous tradition. It has significant negative impacts on mortality and morbidity, both for the person directly concerned and for her children and family. The practice of FGM has immediate, sometimes even lethal, impact and also has implications for her whole life (personal health and socio-economic), if the person survives the initial period.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) summarizes the hazards of FGM in this way:

No health benefits, only harm

FGM has no health benefits, and it harms girls and women in many ways. It involves removing and damaging healthy and normal female genital tissue, and interferes with the natural functions of girls’ and women’s bodies. Generally speaking, risks increase with increasing severity of the procedure.

Immediate complications can include:

- severe pain

- excessive bleeding (haemorrhage)

- genital tissue swelling

- fever

- infections e.g., tetanus

- urinary problems

- wound healing problems

- injury to surrounding genital tissue

- shock

Long-term consequences can include:

- urinary problems (painful urination, urinary tract infections);

- vaginal problems (discharge, itching, bacterial vaginosis and other infections);

- menstrual problems (painful menstruations, difficulty in passing menstrual blood, etc.);

- scar tissue and keloid;

- sexual problems (pain during intercourse, decreased satisfaction, etc.);

- increased risk of childbirth complications (difficult delivery, excessive bleeding, caesarean section, need to resuscitate the baby, etc.) and newborn deaths;

- need for later surgeries: for example, the FGM procedure that seals or narrows a vaginal opening (type 3) needs to be cut open later to allow for sexual intercourse and childbirth (deinfibulation). Sometimes genital tissue is stitched again several times, including after childbirth, hence the woman goes through repeated opening and closing procedures, further increasing both immediate and long-term risks;

- psychological problems (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem, etc.).

(excerpted from WHO (2016) Factsheet on Female Genital Mutilation, which offers a summary of the rationales for, and consequences of FGM.)

More direct reportage (USA report, but could be helpful in community settings?) can be found here:

- What is female genital mutilation? (US Guardian, May 2014)

and here (if you yourself would like to add any other comments or observations for others to consider):

- Why Does Female Genital Mutilation Occur And What Are Its Impacts? (my website, updated as required)

As well as serious personal health impacts for the woman / mother, FGM also imposes significant risks for her children, both during childbirth and later:

These studies indicate that FGM adds another one or two perinatal maternal deaths per 100 deliveries, and that risks are greater with more severe forms of the mutilation, for both mother and child.

Obstetric fistula – a lifelong (and life-limiting) affliction unless repaired – is another very serious risk arising from the combination of FGM, early marriage and premature child-bearing. The cutting may cause the vaginal outlet and birth canal to become constricted by thick scar tissue, thereby increasing the likelihood of gynaecological and obstetric complications, including prolonged labour and fistula. Few reliable statistics are available, but these practices may increase the likelihood of such complications by up to seven times.

In addition, the health and well-being of mothers – assuming they live – is critical also to the well-being of their children.

SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS OF FGM

It is self-evident that people with sub-optimal health find it harder to make the best contributions to their communities. This applies as much where the lack of wellbeing and ill-health (physical and psychological) is because of FGM as in any other circumstance.

FGM results in girls leaving school very young, it may be followed by dangerously early ‘marriage’ and childbirth, it is a factor in mobility problems (broken bones from the time of ‘cutting’), psychological trauma and dislocation, anaemia, recurrent infections, obstetric fistula and maternal mortality, generally shortened life expectancy and much else.

FGM is also very dangerous for infants – boys and girls – at the time of birth, and is damaging to children in their early years if their mother is sick, or dies: Infant Mortality Rates are significantly higher for children whose mothers die or cannot function fully as care-givers.

- The Global Economics Of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) (Burrage blog, February 2014) – traditional communities

- The Real Economics Of FGM: It’s (Much) More Than ‘Wages’ (Burrage blog, April 2014) – Western societies

Hazel Barrett gives an example of the impact also of FGM ceremonies on a local economy in her narrative in Female Mutilation.

There have been proposals (eg by the late Efua Dorkenoo in her seminal book Cutting the Rose, and by others elsewhere in my book Female Mutilation) that Western aid for health programmes in developing countries should be made to some extent dependent on evidence that FGM is being addressed. The opportunity costs and loss of FGM to communities and nations (and global health) are enormous but have as yet hardly been considered.

RATIONALES (‘REASONS’) FOR THE PRACTICE OF FGM

‘Reasons’ for the practice of female genital mutilation vary both between locations and over time, as do the details of the act itself.

FGM was probably first introduced about 3-5,000 years ago, in ancient Egypt, as a way of controlling women – both those in wealthy families where lines of inheritance have always been important, and female slaves whose fertility their owners sought to regulate for commercial reasons.

- Facts about: Female genital mutilation (WHO / IRIS, 2013)

FGM pre-dates all the major religions, even though it is more prevalent in some forms of Islam (not all) than in other faiths. It occurs in communities on every continent in the world, not ‘just’ Africa / SE Asia.

- The Islamic view on female circumcision (African Journal of Urology, 2013)

FGM is fundamentally rooted in economic patriarchy – it is about women and girls as chattels (the property of men, who have ultimate jurisdiction over the allocation of community assets). In almost all cases FGM is arranged by the women, who fear their daughter will be unmarriageable unless they can be ‘proven’ to be ‘pure’ (ie virgins, upholding the honour and virtue of themselves and their families).

- Patriarchy Incarnate: The Horrifying Practice of Female Genital Mutilation (RinGs / Burrage, 2016)

For girls and women to have (economic) ‘worth’ they must be ‘pure’ – which is believed to be achieved by FGM; girls are a family investment, sold by their fathers to their prospective husbands (sometimes as one of several wives). In most traditional societies marriage is essential for women; it is the way they will be provided for as adults in communities where women usually have little formal power and few resources of their own.

Girls may not be permitted – let alone encouraged – to stay on at school, because the family investment in them is traditionally only to sell them to marry, often very young, for a dowry (bride price). The marriage, at least in theory, then provides a ‘pension’ for the girls’ family of origin parents. And the young women become, as some are on record as observing, baby machines.

By tradition this arrangement is non-negotiable; without marriage prospects for women are grim. Marriage and female dependency provide a very effective mode of controlling women (which perhaps also explains the huge resistance to ‘gay’ / homosexual relationships noted in many traditional societies).

PREVALENCE AND DATA-COLLECTION (CHALLENGES)

Attempts to assess the global prevalence of FGM, and to establish its occurrence in different countries and communities, continue. There is however the obvious problem that FGM is increasingly an activity shrouded in secrecy – especially in eg Asian societies, and now also in many nations around the globe where the practice is illegal.

Estimates of global prevalence have in fact been substantially increased in early 2016, to accommodate the realisation that FGM has been a ‘hidden’ tradition in several countries outside Africa.

- Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: a global concern (UNICEF, 2016: ‘UNICEF’s data work on FGM/C’) – gives considerable technical detail about how the figures are determined

- At least 200 million girls and women alive today living in 30 countries have undergone FGM/C (UNICEF, 2016)

In the UK (England, specifically) overall statistical data is now being collected from hospital etc reports to ascertain the locations and prevalence of FGM; obviously, these data reflect the prevalence only in those who present with clinical conditions (of any sort) where the FGM can be observed.

- Health and Social Care Information Centre Female Genital Mutilation Datasets (UK Government Department of Health, from 2015)

The challenges and complexities of establishing the prevalence of FGM are discussed in this paper:

- Estimating the numbers of women with female genital mutilation in England and Wales (Macfarlane and Dorkenoo, 2015)

The new British reporting mechanisms will however provide at least some level of confidence in establishing the likely prevalence of FGM in various parts of the UK, and the methodologies suitably adapted can be utilized elsewhere.

LEGAL STATUS OF FGM

FGM is recognized internationally as a violation of human rights, and as child abuse. As this briefing document, amongst many others, states, ‘the practice also violates a person’s rights to health, security and physical integrity, the right to be free from torture and cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment, and the right to life when the procedure results in death.’

and, for international formal positions

- International Agreements (IAC, updated 2016)

The illegality of FGM is enshrined in the laws of almost all nations around the world, both through prohibitions on assault and bodily harm (virtually universal, whether in national or religious law) and often also in FGM-specific legislation (see Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation, pp 150-153).

Amongst the traditionally practising nations (or with practising communities within them) which now overtly prohibit FGM are Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Cote d’Ivoire, Djibouti, Egypt (with some vacillation), Ethiopia, The Gambia (very recently, as a result of campaigning) Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Iraqi-Kurdistan, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria (also very recently), Senegal, Somalia, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda and Yemen, see

- National Laws on FGM (IAC, updated 2016)

All Western nations have some statutes which implicitly or explicitly outlaw FGM (see also pp.152-153 above). Amongst those with the most specific prohibition is the UK, but France – which has seen many successful prosecutions – has made important progress via more generic legislation against bodily harm. The USA (a complicated example, because of its numerous semi-autonomous states) in general lags behind most other Western countries in acknowledging FGM overtly within the legal framework. Australia, significant particularly because of its geographical proximity to nations where FGM is practised ‘below the radar’, also has different statutes in different states.

In the UK there has been considerable progress on the human rights aspects of FGM – the UK Bar (legal association) has an FGM Human Rights Committee which has pressed for, and obtained, a range of specific and enabling legislation. Nonetheless, there have still been no successful UK prosecutions, and many challenges remain:

- 10 reasons why our FGM law has failed – and 10 ways to improve it (Dias, Gerry and Burrage, Guardian, 7 Feb 2014)

In both traditionally practising and Western nations the formal position that FGM is illegal remains poorly followed through – albeit that countries across the globe, from Kenya (where the first prosecutor specifically for FGM was appointed some two years ago – see my book Female Mutilation) to the UK, are now paying more attention to the challenges of law enforcement.

Within the global community of activists against FGM the position has however become very clearly articulated, as is evident from the annual event, first established to note the declaration against FGM on 6 February 2003, led by the First Ladies of Nigeria, Burkina Faso, Guinea Conakry and Mali with other members of the Inter-African Committee on Harmful Traditional Practices.

- Zero Tolerance Day (IAC, 2012)

Each year a different theme appropriate to the remit of #EndFGM is adopted –

Statements which take this #EndFGM message forward include

- The Bamako Declaration (IAC, 2005)

TERMINOLOGY

The UNFPA (2015) adopts a human rights perspective, stating that the correct terminology in formal contexts is Female Genital MUTILATION:

Quote: Why are there different terms to describe FGM, such as female genital cutting and female circumcision?

The terminology used for this procedure has gone through various changes.

When the practice first came to international attention, it was generally referred to as “female circumcision.” (In Eastern and Northern Africa, this term is often used to describe FGM type I.) However, the term “female circumcision” has been criticized for drawing a parallel with male circumcision and creating confusion between the two distinct practices. Adding to the confusion is the fact that health experts in many Eastern and Southern African countries encourage male circumcision to reduce HIV transmission; FGM, on the other hand, can increase the risk of HIV transmission.

It is also sometimes argued that the term obscures the serious physical and psychological effects of genital cutting on women. UNFPA does not encourage use of the term “female circumcision” because the health implications of male and female circumcision are very different.

The term “female genital mutilation” is used by a wide range of women’s health and human rights organizations. It establishes a clear distinction from male circumcision. Use of the word “mutilation” also emphasizes the gravity of the act and reinforces that the practice is a violation of women’s and girls’ basic human rights. This expression gained support in the late 1970s, and since 1994, it has been used in several United Nations conference documents and has served as a policy and advocacy tool.

In the late 1990s the term “female genital cutting” was introduced, partly in response to dissatisfaction with the term “female genital mutilation.” There is concern that communities could find the term “mutilation” demeaning, or that it could imply that parents or practitioners perform this procedure maliciously. Some fear the term “female genital mutilation” could alienate practicing communities, or even cause a backlash, possibly increasing the number of girls subjected to the practice.

Some organizations embrace both terms, referring to “female genital mutilation/cutting” or FGM/C.

What terminology does UNFPA use?

UNFPA urges a human rights perspective on the issue, and the term “female genital mutilation” better describes the practice from a human rights viewpoint.

Today, a greater number of countries have outlawed the practice, and an increasing number of communities have committed to abandon it, indicating that the social and cultural perceptions of the practice are being challenged by communities themselves, along with national, regional and international decision-makers. Therefore, it is time to accelerate the momentum towards full abandonment of the practice by emphasizing the human-rights aspect of the issue.

Additionally, the term “female genital mutilation” is used in a number of UN and intergovernmental documents. One recent and important such document is the first UN General Assembly Resolution (UNGA Resolution 67/146) on “Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilations.” Other documents using the term “female genital mutilation” include: Report of the Secretary-General on Ending Female Genital Mutilation, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council: Towards the elimination of female genital mutilation, Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa; Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action; and Eliminating female genital mutilation: An interagency statement. And each year, the United Nations observes the “International Day of Zero Tolerance for Female Genital Mutilation.”

– See more at: FGM: FAQs (UNFPA, Dec 2015)

A document which offers further detail about the development of these positions is

- A Feminist Statement on the Naming and Abolition of Female Genital Mutilation (important background details here)(2013)

In formal dialogue, any term except ‘Mutilation’ is a euphemism and may diminish recognition of the harm which FGM inflicts. Of course familiar and inoffensive terminology must be used with patients and survivors where they want that, but there are, for example, no medical conferences about what patients may call ‘Waterworks’; rather, clinicians discuss ‘Urology’.

Despite trends in eg the USA, where anthropologists and others have preferred more euphemistic terms such as ‘Cutting’, it is time now for professional dialogue to employ only the terminology which organisations such as the Inter-African Committee use – ie ‘Mutilation’ – See Dr Morissanda Kouyate, Executive Director of the IAC on this subject:

NB Computer-translated (rather approximately) from the original French…

Quote: For us in Africa, we recognize without complex, the practice of mutilating female genitalia for cultural or non-therapeutic purposes is called GENITAL MUTILATION.

Any understatement of the kind FGC [‘Female Genital Cutting’] despises pain and violation of the rights of girls and women who are victims.

[There are] Seven fundamental reasons governing the choice of FGM against FGC.

- In theEncyclopedia Britannica, the term mutilation is defined as partial or total amputation of a limb or organ partial or total destruction, degradation of an organ.I did not find any other words that best describe the practice of FGM… A young Guinean woman said to me:

“You do not need to explain the harmful effects of FGM in their consequences, women who have suffered; practice is sufficient in itself to be classified as the most serious thing, just before death I say this also because I do not know as deeply death.”

Would I have the courage to explain to this lady that some think it was simply cut and not mutilated?

- The World Health Organization whose immense work in this area should be welcomed here and that is the specialized United Nations health, so the international reference, has classified FGM into 4 types :

- The first involves the excision of the prepuce with or without excision of part of the clitoris

- The second is the clitoris with part or all of the labia minora

- The third is the removal of the external genitalia (clitoris, labia majora and minora) followed by suturing the banks.

- The fourth varies in a range of different acts: drill, cauterize, scratching genitals or the anus introducing corrosive substances and / or herbs and infusions in the genitalia of girls and women etc.

All four types are designed for one purpose: to destroy, damage the female genitalia. Each type is a process that includes several acts including cutting and suturing it is illogical to replace a process by one of the acts that compose it. FGC saying this is what we do. And also in the fourth type, it is often cut anything. In this case we could also talk about MGP (Female Genital Piercing).

- The Inter-African Committee composed of 28 African countries where FGM is practiced, which is the pioneer organization in Africa in the fight for the elimination of FGM, made two important statements saying the term was one that MUTILATIONS describing best practice in the health scale, social and legal. It is important for anyone who wants to help Africans get rid of this scourge, to respect the choice of victims and African actors.

- The international community (UN) in Resolution A / RES / 53/117 of 1 stFebruary 1999, its General Assembly and in all its official documents, spends the term ” GENITAL MUTILATION ”.

The Protocol to the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights on the Rights of Women in Africa designed by the African Union, adopted on 11 July 2003 by all African Heads of State, embodies the term mutilation: genital Mutilation (FGM).

Having thus succeeded in engaging African and international political leaders at the highest level in the fight for the elimination of FGM, it would be extremely serious back distract them with a name change for purposes unexplained and unacknowledged.

- In December 2005, the Inter-African Committee brought together religious leaders (Christians and Muslims) from 28 member countries. This important symposium was crowned by a declaration which strongly condemns female genital mutilation (FGM) because the Scriptures prohibit all forms of mutilation. They subsequently created the network of African religious leaders against FGM and to defend the rights of women and children.

Despite this success, minority religious fundamentalists continue to support FGM as a religious requirement One of their arguments is that it is an exaggeration to say that the practice is a mutilation. For them it is to cut a small part of women to cleanse without intent mutilating. That’s how the arguments of religious fundamentalists perfectly match those of the proponents of the concept FGC. For each other, the term mutilation is an exaggeration.

Intellectuals critics of the struggle for the elimination of FGM, declare that it is a movement came from Western countries and imposed on Africa over the last twenty years of outreach and advocacy, we managed to prove that the protection of the lives and rights of women and girls in Africa is a sacred duty for all endogenous African. This is what has helped the Inter-African Committee to achieve important results, but fragile.

Going back to our people with a new name (FGC) manufactured in the North (by Westerner) is to bring water to the mill of the proponents of the theory of imported ideas.

- The human, material and financial resources that will be used for this new media and semantic campaign seeking to replace MUTILATIONS by CUTTING / CUTTING could be invested in the campaign to save thousands of African girls who are potential victims.

Revise the technical, legal and political texts with the serious consequences that will result in simply to replace MUTILATIONS by CUTTING / CUTTING would be an immense task with insignificant results, ladles and compromising.

By changing the name, we should not be surprised that the statutory and legal texts lapse especially when they are handled by competent counsel in the position of defending the perpetrators of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)….

Let us be vigilant and mobilized because in the near future, conditionalities of funding projects to fight for the elimination of FGM will be established in relation to the use of terms and MUTILATIONS CUTTING / CUTTING. Those who have not put MUTILATIONS CUTTING / CUTTING in their project documents will be deprived of some funding, although the shortfall will expose thousands of girls to female genital mutilation (FGM).

Spend our energy, our knowledge and all our resources to educate our communities to put an end to female genital mutilation (FGM) by knowingly. During this gigantic work, we avoid wasting to theoretical and metaphysical distractions….

Because we must have the courage to ask the equation FGC = FEMALE GENITAL CONFUSION

FGM AND MALE ‘CIRCUMCISION’

Debates about the similarity or otherwise of FGM and male circumcision (also called male genital mutilation, MGM) continue to add complexity to the issues. On one hand, the case can be made – rightly in the view of many present-day observers – that both are human rights abuses (at least when performed on minors) and on the other, the history, rationales and the relative damage caused by each is debated:

- History of Circumcision (Robert Darby website, mostly undated)

and, very importantly,

- Genitale Autonomie (Levin, 2014 – video, in English)

Beyond this however are the issues and debates arising from the current advice that medical male circumcision is a successful way to reduce the risk of HIV in eg some African communities.

- Male circumcision and AIDS / HIV: challenges and opportunities (Sawires et al, 2007)

- The Use of Male Circumcision to Prevent HIV Infection (Statement by Doctors Opposing Male Circumcision, 2008)

Even however if the programme to prevent HIV in males does demonstrate significant success, and even if the physical and psychological damage is much less than in some ‘traditional’ settings – deaths of traditionally circumcised young men occur every year, as for some does major harm – available data suggests the analysis to date has been largely ungendered, or has focused on the connections between male and female circumcision as ways to control HIV infection:

- Circumcision and HIV Infection (CIRP, 2014)

There has to date been only very limited consideration of this HIV prevention programme’s impact on risks to females. Evidence is however now coming to light that there are serious misunderstandings by the women in some communities, and even that campaigns to eradicate FGM are being damaged by local traditionalists’ protestations that medical advice ‘lets’ men be circumcised, but doesn’t permit women to undergo cutting.

- Making Medical Male Circumcision Work For Women (Women’s HIV Prevention Tracking Project, Uganda, 2010)

- Female Mutilation: Chapter 9, Hazel Barrett, p.123 (Burrage, 2016)

Quote: My research … shows that many FGM-affected communities equate FGM with male circumcision, in terms of traditional practice. In fact very oftenthe same local word is used to describe both. Many communities cannot understand why it is legal in the EU [Europe] to perform male circumcision, yet illegal to do FGM. They see this distinction as a form of discriminationagainst girls and women. The failure to tackle the issue of male circumcision is undermining the fight to end FGM.

CLINICAL APPROACHES AND TREATMENT

General clinical care considerations

- Female genital mutilation: The Prevention and Management of the Health Complications – Policy Guidelines for nurses and midwives (WHO, 2001)

- Female genital mutilation: integrating the prevention and the management of the health complications into the curricula of nursing and midwifery A student’s guide (WHO, 2001, also in French; a Teacher’s guide is also available)

Care of the genitally ‘cut’ patient at risk is not however a matter to consider only in respect of obstetrics, as, for example, this considered paper on HIV and traditional harmful practices shows:

- Traditional Cultural Practices and HIV: Reconciling Culture and Human Rights (Day and Malleche, 2011)

also

- RCOG release: Updated guidelines provide clarity for healthcare professionals on the care of women with FGM (RCOG, 2015)

- Female Genital Mutilation and its Management (RCOG, 2015, Greentop Guideline No 53)

- Review: Obstetric management of women with female genital mutilation (FGM) (RCOG, Rashid, 2011) (One important aspect of this paper is the discussion of mortality rates and thei causation – more research, to help/inform prevention strategies, is required on this difficult topic.)

- FGM Treatment (UK, National Clinical Group, 2015 – includes, as do most of the refs above, psychological issues, legal / safeguarding aspects and NHS clinic etc provision)

- RCN FGM Guidance (especially on sexual and travel health etc)

Despite all these documents / reviews, major challenges must still be confronted when it comes to the knowledge about FGM of clinical and other health-care professionals:

- Review Paper: A mixed-method synthesis of knowledge, experiences and attitudes of health professionals to Female Genital Mutilation (Reig-Alcaraz et al, Journal of Advanced Nursing, 2015)

- Female Genital Mutilation: perceptions of health care professionals and the perspectives of the migrant families (Kaplan-Marcusan et all, BMC Public Health, 2010)

Remediation

Remediation of FGM includes a variety of procedures to repair damage, either immediately after the mutilation (eg to stop haemorrhage) or to increase comfort and bodily function at a later date. It also includes surgery specifically to enable safe childbirth (see above) and, more controversially in the eyes of some, repair and reconstruction to establish or reinstate sensation via the clitoris – which is a much bigger organ than was previously thought:

- Anatomy of the Clitoris: Revision and Clarifications about the Anatomical Terms for the Clitoris Proposed (without Scientific Bases) (ISRM Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2011)

- Beyond the G-spot: clitourethrovaginal complex anatomy in female orgasm (Nature Reviews Urology, 2014 – includes commentary on potential damage even from clinically informed surgery etc.)

Reconstruction (clitoroplasty) techniques have been developed by in Europe, the USA and now in a very few locations in Africa, largely led by the work of surgeons such as Pierre Foldes MD:

- Reconstructive Surgery Corrects Female Genital Mutilation (Medscape, 2012)

- FGM: Tackling a trauma (Anna Feist, 2015 – in Germany)

- First FGM Victims Successfully Operated in Sweden!! (Desert Flower website, 2015)

- FGM Repair / Clitoral Reconstruction (Dr Marci Bowers website, USA and Burkina Faso)

Clitoral reconstruction (clitoroplasty, as opposed to simply surgical repair) is a relatively new development considered by some more appropriate in the First World, as these reports demonstrate:

- Position statement regarding clitoral reconstruction (FGM National Clinical group, 2014)

- FGM Repair/ Clitoral Restoration (Under the Scope, 2014)

Reconstruction is not a universal panacea for FGM, but it can have very positive outcomes:

- FGM Victim Tells About Reconstructive Surgery (Waris Dirie/ Desert Flower website, Feb 2016)

The debate about how helpful or relevant in traditional settings the idea of women’s sexual pleasure can be – even where the concept is actually recognised – is at an early stage. This is particularly because discussion of intimacy of any sort is often taboo, and men and women do not consider such matters together – which is also a reason that both sexes may suppose the other ‘requires’ FGM in the first place, even when a majority of neither men nor women actually does want it to continue.

ERADICATION

General issues / background

A ground-breaking, and now historic, case for the eradication of FGM was made by the late Fran Hosken, a very committed and straight-talking campaigner, in 1989:

- Female Genital Mutilation: Strategies for Eradication (Hosken, 1989)

Since that time (1989) vast numbers of documents have been produced on this subject, most of them with now out-dated figures, including

- Eliminating Female Genital Mutilation: An interagency statement OHCR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO, UNFPA, UNHCR, UNICEF, UNIFEM, WHO (WHO, 2008) (language options) / PDF format

- Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change (UNICEF, data of prevalence up to 2011)

- Ending Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Lessons From a Decade of Progress (US Population Reference Bureau, 2014)

For a more country-specific approaches, eg (amongst many case studies):

- Eradicating female genital mutilation and cutting in Tanzania: an observational study (BMC Public Health, 2015)

- Curbing the surge of female genital mutilation (Odeku, Bangaldesh e-Journal of Sociology, 2014)

- Eradication of female genital mutilation in Somalia (UNICEF, nd)

- JAPAN: In Solidarity Against Female Genital Mutilation (IPS News, 2006)

- Anti-Female Genital Mutilation Safe-Camp in Tanzania (Riva Refuge, nd)

- UK leads the way to eradicating female genital mutilation (UK Government, 2015)

If we are to eradicate FGM it is essential that the ‘reasons’ for it are understood – and that the big variations in both rationales and actual practice between different communities are also recognised. FGM is chameleon in the ways its rationales and ‘procedures’ change and adapt over time; but the harm is consistent, eg:

- The challenge of eradicating FGM among Kenya’s Maasai (Andrew Wasike, DW, Feb. 2016)

- Female Genital Mutilation – is zero tolerance the right approach? (PodAcademy, 2014)

Legal and Protection

Following a public consultation, a new mandatory reporting duty for FGM was introduced in the UK via the Serious Crime Act 2015. The duty requires regulated health and social care professionals and teachers in England and Wales to report known cases of FGM in under 18-year-olds to the police.

- Mandatory reporting of female genital mutilation: procedural information (Home Office / Department for Education, October 2015)

- FGM Guidance for professionals (NHS, 2015 – includes professional video advice)

The reporting procedures are however by no means ideal, and have left some professionals uncertain about how effective the requirements now established will be, eg:

Campaigning / community

In almost every corner of the globe there are many large and smaller organisations which campaign against FGM, as well as many individual campaigners, quite a lot of them survivors or people who are connected with survivors. [Some of these organisations and individuals, globally and in the UK, are mentioned in my books, as below.]

Coordination between these various interests is however hampered by the realities which confront NGOs and campaigning individuals ‘on the ground’:

- resourcing / funding is difficult to obtain,

- professionals / officials may not be comfortable liaising with volunteers and others they may see as ‘amateur’,

- small campaigning organisations, and individuals (especially survivors), may feel uncomfortable about, or even resent, the status and influence of the professionals, whom they perceive as having little understanding of the issues around FGM.

The challenges of ensuring

- that officials and professionals are sensitized, whilst also focused on prevention / eradication,

and

- of appropriate support / training for volunteers / campaigners,

have not to date been widely recognized or addressed.

Men (and community campaigning / impact)

Much of the work on FGM eradication has been done by women, but it is obvious that the opinion of men is also critical. In many communities they have the final say, and women often inflict FGM on their daughters because they believe that men will not marry a girl who is ‘uncut’.

- Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: The Secret World of Women as Seen by Men (Kaplan et al, Obstetrics and Gynaecology International, 2013)

Quote: Seen through men’s eyes, the secret world of women remains embedded in cloudy concepts shapd by culture in ethnic tradition, also influenced by religion. All ethnicities in this study [the Gambia] follow Islam, but each of them establishes a different relation between FGM/C and religion….

Slowly, men are becoming more engaged in decisions to stop FGM – in fact, the Gambian / American campaigner Jaha Dukureh recently managed to have FGM made illegal in Gambia, following pleas to her father, a powerful chief in that country:

- One woman’s journey to American Dream includes a crusade (CNN, January 2016)

And in other parts of the world too, young men are leading campaigns to eradicate FGM (see Female Mutilation, Burrage, 2016, below).

- Patriarchy Incarnate: The Horrifying Practice Of Female Genital Mutilation (LSHTM / RinGs, Burrage, 2016)

It is patriarchy, however that concept / ideology is defined and presented, which bolsters the continuing practice of FGM; in that deeply embedded tradition women and girls are ‘owned’ by men and are in effect chattels (objects). Increasingly, it is understood that only when men too stand up against FGM will it finally stop.

- A Feminist Statement on the Naming and Abolition of Female Genital Mutilation (website – see also Background)

The gendered (male) aspect is also one of the reasons why politics is very significant in the abolition of FGM. Some women may have significant influence (eg the grandes dames, the Sowei – custodians of the all-women Sande Society* – in parts of Africa), but the most powerful politicians in most countries (and communities) are men. [*See Sande Society, Wikipedia]

The appeal by Ban Ki-moon, the United Nations Secretary General, that men be involved in efforts to eradicate FGM is therefore very apposite:

- Ban Ki-Moon calls on men across the world to campaign to end FGM (O’Kane, Guardian, 6 Feb. 2012)

Education

The first focus in eradicating FGM is ‘prevention not prosecution’ (alongside full support and assistance for those who have undergone the damage). Clearly, education plays a big part in prevention. It comes in various forms:

- Explaining that most women and girls are not ‘cut’ – which may not be known by those who are, or by their families / fellow community members

- Information about female anatomy and self-care (including provision of ways to manage menstruation – which, unaddressed, can prevent school attendance)

- Information about reproduction and sexuality (discussion of sexual matters is often taboo in traditional communities)

- Encouragement and incentives to enable girls to continue their schooling and, like their brothers, to aim for economic autonomy as adults

- Campaigns to prevent child, early and forced ‘marriage’

- Information for older girls about how to avoid / escape FGM if it is threatened

- Reinforcement of the fact that no religion ‘requires’ FGM (where this is relevant)

- Information about the illegality of FGM, and the penalties for doing it, etc

Alternative Rites of Passage (ARPs) – also Education

In communities where FGM is (still) a rite of passage, such as in the Maasai and Samburu tribes of Kenya, there is now increasing success with programmes of Alternative Rites of Passage (ARPs), where the entire community is involved in learning about the perils of FGM and the benefits of continuing education. At the end of the programme (usually quite brief, once the agreement to engage has been secured) there are special ceremonies which contain many of the same elements as the previous FGM coming of age events, but without the harm. See eg (amongst many possible examples)

- ‘I witnessed FGM. That’s why I know we need to talk about it’ (Domtila Chesang, The Guardian, 5 Feb 2016)

- Beyond FGM (website about #EndFGM programmes in Pokot, Kenya, with Domtila Chesang and UK midwife Cath Holland)

More formally, education about and protection n FGM is clearly also a role for schools.

The case is consistently made, especially in Western nations, for compulsory Personal, Social and Health Education / Sex and Relationship Education, but the UK Government amongst others continues to resist.

- Sex and Relationship Education for the 21st Century (PSHE Association, Supplementary Guidance)

Likewise, in the UK, Local Safeguarding Children Boards have been introduced, but they are not well funded or statutory for active engagement by schools.

Health

One encouraging development in the UK was the Chief Medical Officer’s 2014 Report, which includes a chapter on FGM:

- Chief Medical Officer annual report 2014: women’s health (Dame Sally Davies, Dept of Health, 2015)

Many of the documents cited above address issues around FGM and clinical management / heath care.

- TOOLKIT: Midwives committed to the abandonment of FGM – ENGAGING MIDWIVES in the Global Campaign to End Female Genital Mutilation (UNFPA, ?2015)

Importantly, as many of the previously mentioned sources also suggest, there are still numerous questions to be answered, and issues to be resolved, before FGM can be fully eradicated.

- Research gaps in the care of women with female genital mutilation (FGM) (WHO, 2015)

Readiness for change

Whilst FGM is illegal almost everywhere, communities in different parts of the world are not all as yet ready to abandon the practice. Our knowledge of how to assess stages of readiness to abandon FGM is growing, as this paper (arising from the European REPLACE2 programme) demonstrates. Different approaches to eradication are required at different levels of readiness:

- The Applicability of Behaviour Change in Intervention Programmes Targeted at Ending Female Genital Mutilation in the EU: Integrating Social Cognitive and Community Level Approaches (Brown, Beecham and Barrett, 2013)

We can expect that the ‘readiness for change’ approach will be used more in the future, now that techniques for measuring readiness have been developed by Barrett et al.

Multi-agency or Inter-disciplinary?

There is near-universal agreement that many agencies must be involved in the eradication of FGM, whether at the local, national or international level. This understanding is articulated by numerous global organisations (WHO, UNFPA etc, as above) and in the UK via documents such as:

- Female genital mutilation: multi-agency practice guidelines (UK Government, 2014)

I would argue however that this approach, although necessary, is not adequate as a response to the challenges of FGM. Beyond the rhetoric of the ‘multi-agency approach’ there is a fundamental requirement also for an integrated discipline with shared understandings between all who seek to combat FGM:

- A Global Paradigm For ‘FGM Studies’ (Burrage blog, 2016, also here)

Even the issue of terminology is not yet fully agreed between the various parties to FGM eradication:

- Anthr/Apological Studies Of FGM As Cultural Excuses For ‘FGC’ (Burrage blog, 2015 includes statements by the Inter-African Committee, the Royal College of Midwives and the UNFPA – See also Statement on FGM as above)

Speedy eradication is imperative

Despite all these initiatives and considerations, FGM continues to be a global epidemic.

It has been estimated that one woman dies every ten minutes from the sequelae of FGM:

- Obstetric management of women with female genital mutilation (Rashid and Rashid, 2007)

The message is therefore clear….

- No Time To Lose: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (UNICEF, 2014 – video)

Quote (UNICEF 2016):

CURRENT PROGRESS IS INSUFFICIENT TO KEEP UP WITH INCREASING POPULATION GROWTH.

IF TRENDS CONTINUE, THE NUMBER OF GIRLS AND WOMEN UNDERGOING FGM/C WILL RISE SIGNIFICANTLY OVER THE NEXT 15 YEARS.

* * *

…………………………………………………………………………………………….

TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION

Public Heath

Whilst most work to eradicate FGM has, at least until recently, been undertaken by clinicians – gynaecologists, midwives etc – it may be that the lead should now be taken by Public Health professionals;

Public Health includes all the legal, educational, socio-economic / epidemiological and clinical aspects of ‘social diseases’ such as FGM.

My own view on the role of Public Health in eradicating FGM is explored in some detail here.

What’s your view? Should Public Health take the lead in most places?

Developing FGM Eradication Programmes in Low-Resource settings

The growing use of engagement in traditional communities to abolish FGM includes the APR (Alternative Rites of Passage) approach considered above, as well as programmes such as the ICOD Action Network ‘Barefoot Grannies’ of Uganda:

There is also a new emphasis on the use of social media to promote prevention in especially (but not only) some developing countries. Examples include

- A New App To Tackle FGM (Coventry, UK: REPLACE2 programme; click the ‘Petals’ link to see the App.)

Is this the way forward? How can these relatively low-tech approaches combine with conventional clinical methodologies?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Read more about FGM as Patriarchy Incarnate

Your Comments on this topic are welcome.

Please post them in the Reply box which follows these announcements…..

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Books by Hilary Burrage on female genital mutilation

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6684-2740

Hilary has published widely and has contributed two chapters to Routledge International Handbooks:

Female Genital Mutilation and Genital Surgeries: Chapter 33,

in Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health (2019),

eds Jane M. Ussher, Joan C. Chrisler, Janette Perz

and

FGM Studies: Economics, Public Health, and Societal Well-Being: Chapter 12,

in The Routledge International Handbook on Harmful Cultural Practices (2023),

eds Maria Jaschok, U. H. Ruhina Jesmin, Tobe Levin von Gleichen, Comfort Momoh

~ ~ ~

PLEASE NOTE:

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, which has a primary focus on FGM, is clear that in formal discourse any term other than ‘mutilation’ concedes damagingly to the cultural relativists. ‘FGM’ is therefore the term I use here – though the terms employed may of necessity vary in informal discussion with those who by tradition use alternative vocabulary. See the Feminist Statement on the Naming and Abolition of Female Genital Mutilation, The Bamako Declaration: Female Genital Mutilation Terminology and the debate about Anthr/Apologists on this website.

~ ~ ~

This article concerns approaches to the eradication specifically of FGM. I am also categorically opposed to MGM, but that is not the focus of this particular piece, except if in any specifics as discussed above.

Anyone wishing to offer additional comment on more general considerations around male infant and juvenile genital mutilation is asked please to do so via these relevant dedicated threads.

Discussion of the general issues re M/FGM will not be published unless they are posted on these dedicated pages. Thanks.