Female Genital Mutilation: What We Still Don’t Know … Socio-economics (Water, Land, Knowledge): The Global Backlash

Few would deny that we currently see a global backlash against women’s rights, status and autonomy. This has impeded work to support vulnerable women and to eradicate harms such as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

Few would deny that we currently see a global backlash against women’s rights, status and autonomy. This has impeded work to support vulnerable women and to eradicate harms such as Female Genital Mutilation (FGM).

Addressing this issue, the final 2025 Female Genital Mutilation seminar at Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford, was an International Colloquium on Advocacy and Research on Friday 5 December with the theme The Global Backlash against Women’s Rights: Ending Violence against Women means Halting FGM.

My presentation at the event concerned a socio-economic perspective only infrequently employed directly in efforts to #EndFGM – taking a look at what we still don’t know about the ways FGM continues or may be abated longer term via factors such as women’s access to water, land and literacy / knowledge.

Is there a danger over the coming years that activists’ and others’ current hugely successful interventions to end FGM will fade from collective memory, to be replaced by the forces of reaction (and all that means for tolerance of violence against women)?

Will women and girls become vulnerable again? This is where others in society – everyone from politicians to public health leaders to media commentators – must step in to support, immediately.

At a time when the global zeitgeist is turning against humanitarian interventions these are issues which surely we need to consider?

The observations below are my attempt thus far to bring such concerns to the #EndFGM agenda.

You can read this website in the language of your choice via Google Translate.

Understanding FGM from a Socio-economic Perspective

What We Still Don’t Know … Water, Land and Knowledge

The Global Backlash

I have suggested on many occasions that the physical and socio-economic environments of women and girls vulnerable to FGM are more than merely contexts in some passive mode. These environments surely shape the likelihood of ‘cutting’, both of current (potential) victims of this abuse, and of their daughters’ risk of abuse into the future.

There is now much more understanding of how to reach those who remain unconvinced that FGM is a cruel, never ever acceptable crime. The effort of activists on the ground is compelling wherever it occurs. Their courage and conviction blazes through as they work to finally stop the harm to girls and women.

Certainly the rates of imposition of FGM are stalling in those areas where #EndFGM campaigns are being conducted – albeit absolute numbers of women and girls with FGM have yet to fall – and equally certainly each and every girl and woman spared this harm represents an essential, fundamental victory for human rights and wellbeing.

But are there ways we might enhance this achievement, ways to ensure it endures? Can we respectfully, feasibly and appropriately reshape some of the contexts of these women’s lives so that apparent rationales for FGM become meaningless or irrelevant?

Possible factors influencing FGM and the contexts and environments in which it occurs – the land women live and work on, the water they must fetch every day, the income on which quite often they barely subsist and the knowledge gained in modern times to which they do, or don’t, have access – all require careful consideration.

Difficult questions

My questions are:

- How will we measure the relative efficacy of different factors in ‘success’? By whose criteria should factors and outcomes be evaluated?

- How can factors identified as of significance be actively employed to end FGM? How can any such factors be shared with women (and men) in traditional communities to support the eradication of FGM and, hopefully, enhance the everyday lives of people in these communities?

- How can decision-makers and politicians enable these factors to mesh most effectively with the on-going work of survivors and campaigners on the ground, so that momentum is not lost?

- Is the encroaching global backlash against women a real threat to the total eradication of FGM? And what can we do about it?

Obviously, by no means all these questions can be answered as yet, but asking about some of the factors above may be helpful.

This might, indeed, raise awareness of the need to consider much more overtly the multiple wider contexts of FGM and similar violence. Every girl ‘saved’ is a life remaining whole, but the excellent work to stop FGM must be consolidated over decades before we can claim ‘forever success’.

(And what about the influences on those already harmed? Every FGM ‘survivor’ is also ‘victim’ of a crime, but sadly not all FGM crime ‘victims’ are also personally ‘survivors’… do criteria for these two categories need to be different? What of the impact inflicted or prevented on the wider community? and so forth…)

Water

It has been suggested that the easy availability of clean water reduces the risk of FGM. I have discussed the criticality of water for women and girls here World Water Day – And Why It Matters For #EndFGM and e.g. here Segmenting The #EndFGM Message For Greater Impact – Climate Change, Conflict Displacement, Water, Child Stunting; And Powerful Men.

The extraordinarily shocking fact is that across the globe 200 million hours daily is spent collecting water, mostly by women and girls. This hugely diminishes the time women in already difficult circumstances have available for other ‘duties’ (thereby making them even more vulnerable) and it illustrates the similarly difficult challenges pertaining to female hygiene and dignity.

The 2014 ReliefWeb news report entitled Improved Access to Water May Hold the Solution to Ending FGM in Africa tells us:

… research by Ugandan Gwada Okot Tao [reveals] that ethnic communities that practice FGM in Africa can be found in areas where the water supply is problematic…. in Kenya, for example, only three of the East African nation’s 63 ethnic groups did not practice any form of circumcision. And these three communities were found in the Rift Valley region, where there are water bodies like lakes and rivers. [Gwada] believes that FGM has become a prevalent cultural practice as a consequence of a lack of water.

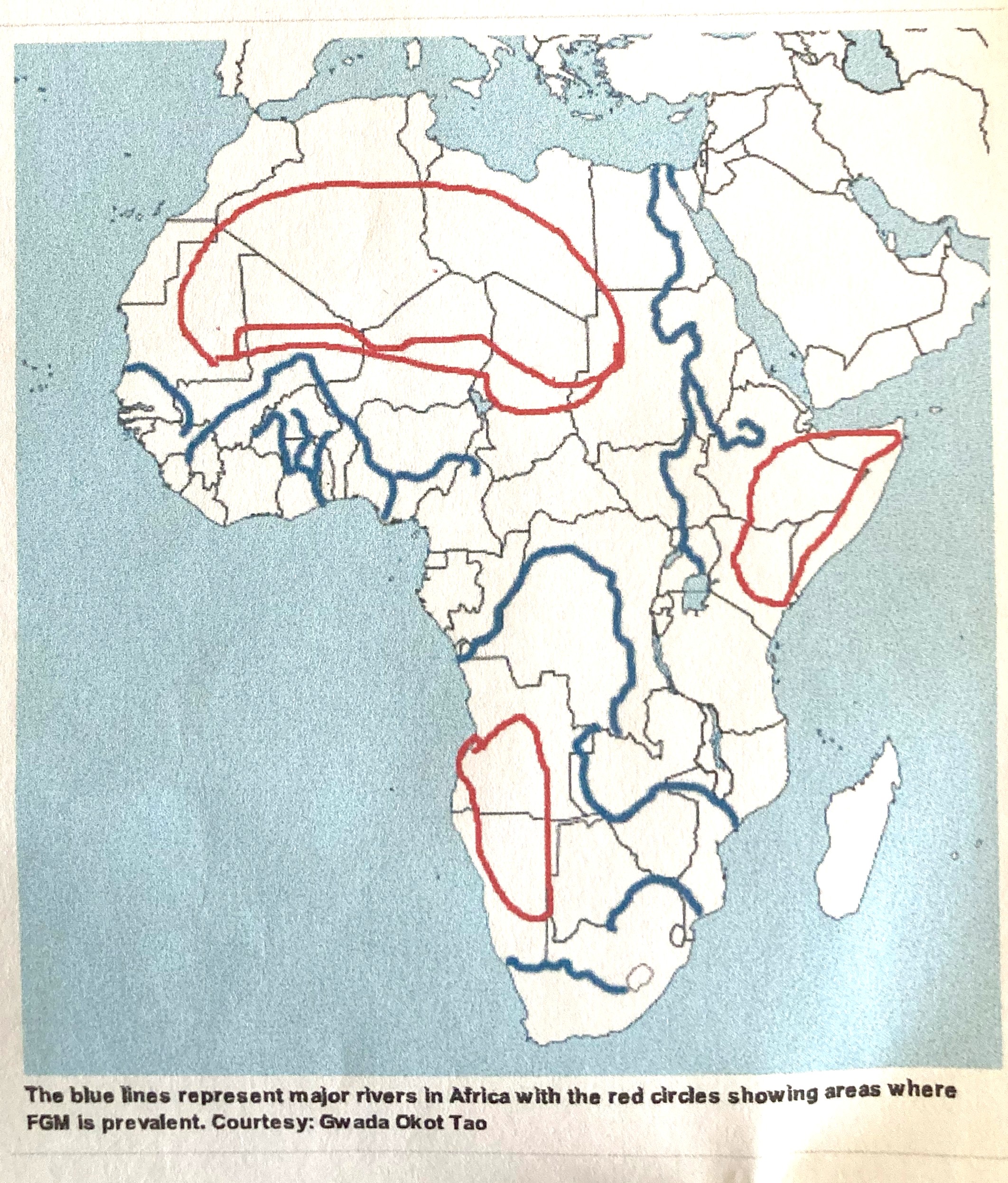

This map by Gwada Okot Tao helps to illustrate why water may be so important. Nonetheless, questions remain:

Why is Egypt a location where FGM remains a serious issue, given that it has a major river system and all parts of the country are closeby (but NB many areas are markedly below the ‘water poverty’ level) – as is true likewise for, say, The Gambia, still beset with a very high rate of FGM (but where wells may be running dry).

Why are aquifers (and other water provision systems) still not a major women’s health focus for ameliorating water issues in places in e.g. Africa, despite the fact that, properly maintained, they may provide a significant amenity and possibly enhance FGM cessation?

Does Gwada Okot Tao have a significant point when he tells us that “Everything is wrong, the policies are wrong, legislation is wrong because they were not informed by what made the communities start the practice in the first place.”?

Does Caroline Sekyewa, the programme coordinator of DanChurchAid, have a point when she says the research finding is convincing because in the communities that practice FGM, a girl who has gone through the ritual is regarded as “clean”… “It may not necessarily mean that the provision of water is the solution to FGM, largely because culture has hijacked the practice, but this could inform the intervention strategies towards its elimination”?

[Both Gwada and Sekyewa quotes are from the ReliefWeb report above; my emphases.)

Do we ask the clearly important questions arising from by Gwada’s and Sekyewa’s observations about water often enough? Is there in current increasingly constrained wider national and international contexts enough space for dialogue to explore ways forward?

Land

In a post in 2020 entitled An Economic Deficit Index for FGM? Human Capital, Sustainable Development And Land I wrote this:

… the matter of gendered land ownership is critical in every corner of our planet, first world or otherwise. In much of the developing world (and quite large swathes of the first world) the question of who owns what land is difficult to answer. The land has always been there, and over the centuries many claims, mostly by men, will have been made on it.

In some parts of the globe however only those considered ‘adult’ may have any stake in the land (and/or perhaps also other property). In this way any women who has not undergone FGM is excluded (and maybe also any man who has not been ‘circumcised‘*). A woman is not ‘adult’ until she has experienced this rite of passage. She may not even be permitted to own any land unless she has been ‘cut’.

[*See also this report on the OHCHR Sande and Poro societies in Liberia, and Onni Gust’s discussion of attaining adulthood, genital mutilation, land and patriarchy in the context of colonialization.]

The title of my Economic Deficit post was ambitious – I am absolutely no eminent economist – but I wanted to bring a focus to the only infrequent consideration of land ownership in discussions of FGM. And so, in a later post, Challenges to Eradicating FGM, I added that women in some places have few rights to the commodities which would enable their economic independence – not least because women are not perceived as having full ‘adult’ entitlements even after FGM (and maybe not at all without it).

Land is often the preserve of men (or ‘granted’ to women on specific conditions), ownership may often be a matter of common understandings, not of legal contract, inheritance goes to other male family members, not e.g. to a deceased husband’s wife, marriage may in any case be an arrangement between one man and two or more women, with all the economic inequities this entails; and often the residue of these customs and understandings remains long after the issue itself may have been at least partially resolved.

These matters require the attention of researchers and politicians, not activists alone. The role of activists in ‘saving’ girls from FGM – especially more recently as part of incredibly impactful whole-community programmes – is vital and increasingly effective, but community beliefs are rarely changed simply and solely by de facto altered realities.

FGM may continue at least sporadically and clandestinely long after it has been formally banished and the law has attended to rights such as the ownership of land. Indeed, FGM may continue particularly in other diaspora locations where it is perceived as a marker of community membership and traditions, as this paper on the ‘migration matrix’ shows. And as the migration matrix paper also explains, people returning to their original location may likewise influence rates of FGM. We are told that interventions to end FGM in refugee settlements can also bear fruit in refugee final country destinations, such as the USA.

It is a stretch from a consideration of land ownership to that of refugee and diaspora status, but perhaps not as much as at first sight. A person (woman) who owns a patch of land has a resource which is to whatever degree difficult in normal times to take away from her; a person who becomes a migrant – perhaps because of conflict or war, or even straightforwardly because her land is parched and no longer produces anything for her – has much less in the way of resources.

Might such a woman revert in some new communities to fitting in by self-identifying via FGM or other harmful ‘traditional’ means? (It seems that in some cases the answer may be yes.) How is this possible ‘second tier’ outcome to be addressed to consolidate on work in long-established communities to end FGM? Is the criticality of legal moves to protect women’s land ownership and its benefits understood by community members as amongst the ‘reasons’ to reject FGM? Have these two aspects of eradication been publicly and clearly aligned?

Or will the increasing perils in these shifting times of climate change, alongside other desperate migration at whatever level, endanger the immediate achievements of some EndFGM programmes? How and by whom, as we continue to promote in every possible way work by activists ‘on the ground’ to eradicate FGM, should these issues be considered?

Knowledge and Literacy

Water and land are obviously better assets when they are utilised with skill and conserved well. In modern times this skill is easier to develop if one is literate and has as a minimum access to other resources such as the internet, tools, etc to enable successful employment of these critical assets.

Women do not always however have the same access to these benefits as men. As the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations reports of subsistence farmers:

To increase rural women’s productive capacity, it is important to endow them with equal land ownership and access to other productive resources, infrastructure and services (such as advisory services, training, finance and information), and to reduce their excessive workloads (such as water and fuel collection). Addressing gender equalities and women’s empowerment are crucial for sustainable land and water management, as well as governance.

Gender disparities in the distribution, tenure, governance and management of natural resources represent a major constraint to achieving sustainable production. Weak land tenure rights hinder women’s access to credit … and lessen their incentives to adopt soil and water conservation measures or uptake climate-smart agricultural practices. Moreover, institutions responsible for water management, such as water users associations or district water authorities, often marginalize or exclude women.

Despite the adoption of gender-sensitive policy and legal frameworks over the last three decades, women’s control and/or ownership of land remained limited, often due to unfavourable marital and inheritance laws, family and community norms, and unequal access to markets. In addition, policies and laws were often not enacted due to the lack of political will, poor institutional capacities and persistent sociocultural discriminatory norms and practices against women.

I consider some of these issues here: Men As Policy-Makers Must Support #EndFGM – Enable Women To Gain Respect As Adults Via Fair Social And Economic Contexts but we need not repeat again what are obvious facts – women and girls in subsistence environments around the world are often underserved and even tragically exploited by the circumstances in which they must survive. They may lack autonomy and self-determination in crucial aspects of their lives.

(And the same may also be true of women who live as almost invisible inhabitants of communities in towns and cities across the globe. In an early (2014) paper I asked whether the act of mutilation itself acts as an excluding mechanism in modern western societies. There are many more brave, visible and open FGM survivors now to mitigate such exclusion than there were then, but this doubtless still applies in some circumstances.)

What may be worth reiterating however is that women and girls need literacy in order to conduct their daily lives in the communities. Literacy is not something only required to work as a doctor, teacher, lawyer or nurse, probably not in one’s location of origin. Literacy, and especially digital literacy, is an essential element of effective efforts to thrive safely in local communities, where most women and girls may want to remain. As one recent study reports:

Lack of digital literacy skills is one of the major challenges that small-scale women farmers face when accessing digital information. Illiteracy is also another challenge that hinders access to digital information and this prompts the small-scale women farmers to prefer the use of traditional information sources that use local languages that they easily understand.

As another report similarly reminds us, there is a need for a gender-sensitive approach in designing and implementing digital tools

But there is also another reason literacy is vitally important, whether in an isolated farming community or a big city: The oral tradition of promoting FGM may, in low literacy communities, over-ride the religious literature which in reality does not promote it. Some religious leaders make serious efforts to persuade their believers away from FGM. Others may prioritise different perceptions of women’s status in their communities, insisting that FGM is a requirement, as the politically difficult situation in The Gambia makes clear.

Looking to the future…

All the situations considered above bring a focus on issues beyond the practise of FGM itself. Yes, hard work and determination in communities can bring about vitally important reductions in the number of girls subject to FGM; and every girl and woman spared this cruel assault is someone who can then lead a safer and more secure life.

Further, as we know, girls who have not experienced FGM are less likely to inflict it on their own daughters. More generally, research suggests that

… daughters are less likely to be cut when parents make key household decisions jointly. Autonomous decision-making by women at the community level was associated with lower odds of daughters being cut. However, at the community level, the impacts of women’s household decision-making were attenuated when FGC was more prevalent.

Here yet again is evidence that women with autonomy are critical to the eradication of FGM. But still we know little about how specific factors such as water and land impinge in agrarian locations on the practice of FGM. Nor is there much discussion of how these particular factors, or others, affect non-agrarian contexts. This is far more than simply a question about education and literacy, absolutely central though these considerations are.

But more generally fears are growing that the trend towards greater autonomy and independence for women (wherever they live in the world) is suffering backlash.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace reports that

In parts of Africa, politicians in socially conservative autocracies and democracies have advanced new restrictions on LGBTQ and sexual and reproductive rights in response to lobbying from domestic and international religious movements. In East Asia, anti-feminist groups in civil society have formed new coalitions with conservative parties and politicians, whereas in South Asia, recent waves of feminist mobilization have catalyzed stronger resistance by ultra-religious and ethno-nationalist movements….

Across Europe, Latin America, and Africa, transnational religious networks (particularly ultra-conservative Christian organizations) have played an important role in driving campaigns against women’s and LGBTQ rights, often under the banner of fighting radical “gender ideology” or defending the “traditional family.”…

New oppositional movements treat gender equality, feminism, and LGBTQ rights as existential threats to cultural and national integrity linked to globalization, Western liberalism, and the erosion of traditional authority. This shared worldview allows diverse actors—from right-wing populists in Europe to nationalist autocrats in Russia and China to conservative religious groups in Latin America and Africa—to coalesce around a common enemy…. Liberal gender norms have become a central target for contemporary illiberal mobilization, functioning as a symbol of everything that is wrong with modern culture and the current world order.

It would surely be surprising if this global trend, in reality misogyny, had no impact on perceptions of FGM.

But the ‘backlash’ is not only about illiberal interpretations of gender issues. It stretches also to straightforward science and medicine. No longer, in some views, is scientific evidence enough to suggest something should be accepted as significant.

Whether considering, for instance, vaccinations or climate change, there is now a strong pushback from some quarters. It would seem that rational appraisal has in various situations now been replaced by skepticism about, or even downright rejection of, ‘the evidence’ that vaccinations save lives, or that current trends in climate change are a threat to the futures of people everywhere.

Focusing on FGM

We do not need here to examine the evidence that FGM is spectacularly damaging to the lives of women, children and communities. We know that.

Nor do we need to dwell on the convincing evidence that programmes to halt FGM are now showing hugely positive results. We know that too.

But perhaps we should also consider more closely the wider contexts in which the backlash against FGM eradication seems to be developing, as we have seen e.g. in The Gambia (where, bolstered by a wider ECOWAS ruling, thankfully, it looks like the Gambian Supreme Court will reject such efforts).

A start here may be to ask questions along the lines of those posed by climate change protagonists. Whether confronting climate change, vaccination ‘hesitancy’ or FGM, we need to know what sort of pushback we face, before we can tackle it. This is helpful analysis, perhaps also applicable to other ‘denials’, of the situation in regard to climate change:

…. this review shows that no advice can be given on how to universally counteract climate denial. For those interested in doing so, however, three guiding questions can be of value:

[F]irst, is it epistemic [refusal to accept credible information, often because it conflicts with a person’s or group’s beliefs, ideologies, or interests] or response denial [refusal to accept the idea] that is to be engaged with? … different strategies are suitable for specific forms of denial, and for specific drivers.

Second, what are the preferred outcomes of a counteraction intervention; is it changing minds, behaviour or policies? If the intention is to increase support for behaviour change or political action … then message framing strategies might be more helpful than inoculation against misinformation…

Third, what is one’s own role – for example, a scientist, expert or politician – and how might it be perceived and the intervention be interpreted? In some cases, using other trusted sources to communicate the message may be necessary.

Everything is complicated in the case of FGM by the underlying, eternally consistent, context of misogyny which serves to accept or ‘validate’ violence against women; but here we are considering how to sustain progress in challenges to this harmful practice.

What sorts of people or, importantly, practical interventions, will likely best maintain and take forward the successes which activists and others have achieved?

Who / which people can most effectively secure support for current programmes of FGM eradication? Even women’s health apart, how might such efforts mitigate the possibility, for instance, that FGM may sometimes give rise to the tragedy of stunted or otherwise harmed children? How are local economies – in any part of the world – improved if women are not harmed by FGM? Which of these questions remains unanswered?

Something to bear in mind as we look to the future is that ‘cultural’ memories are short. Thus, future generations of the original FGM trauma survivors, never having experienced or witnessed the actual events, may perceive things differently from direct survivors, and the cultural / hearsay constructions of these past events may take different shape and form from generation to generation.

One reason vaccination hesitancy has occurred is that barely anyone now recalls the deaths of many children from polio, measles, diphtheria, pertussis and the like. Might the same thing happen regarding FGM, in communities where it no longer occurs? Will (some) people forget what a blight on lives FGM was? Will that make it easier for the forces of misogynistic reaction to insist this cruelty is reinstated?

Consolidating progress

There are no easy answers to these questions. Indeed, the questions themselves have barely as yet been asked; but it is vital at least that they be considered. There is no denying that the backlash against women’s right, status and autonomy is real, and we must face up to that.

Determined campaigns against FGM, often led by survivors and members of their communities, must continue, and support for these campaigns remains absolutely essential.

Beyond that, however, there is a wider context around the enabling of women as independent adults with human rights and, critically, the resources to conduct their lives autonomously, armed with the information and knowledge to do so to best advantage for themselves, their families and their communities. This is where others in society – everyone from politicians to public health leaders to media commentators – must step in to support, immediately.

There are many ways in which men (and women) beyond the inner circle of survivors and activists can support efforts to end FGM. Never has that support been more urgently required and important than now, when at last we are beginning to understand how to tackle FGM at its roots, to prevent FGM and its cruel harm effectively, forever.

.

International colloquium on advocacy and research, Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford, 5 December 2025 – ‘The Global Backlash against Women’s Rights: Ending Violence against Women means Halting FGM’

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Your Comments on this topic are welcome.

Please post them in the Reply box which follows these announcements…..

What We Know About Female Genital Mutilation – A Summary (2025) Of The Many And Complex Aspects

IHPE Position Statement: Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)

Joining The Dots: Why FGM Studies Must Be A Distinct Discipline

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Books by Hilary Burrage on female genital mutilation

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6684-2740

A free internet version of the book Female Mutilation is available

here.

[It is hoped that putting all these global Female Mutilation narrations onto the internet will enable readers to consider them via Google Translate in whatever language they choose.]

Hilary has published widely and has also contributed two chapters to Routledge International Handbooks:

Female Genital Mutilation and Genital Surgeries: Chapter 33,

in Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health (2019),

eds Jane M. Ussher, Joan C. Chrisler, Janette Perz

and

FGM Studies: Economics, Public Health, and Societal Well-Being: Chapter 12,

in The Routledge International Handbook on Harmful Cultural Practices (2023),

eds Maria Jaschok, U. H. Ruhina Jesmin, Tobe Levin von Gleichen, Comfort Momoh

~ ~ ~

PLEASE NOTE:

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, which has a primary focus on FGM, is clear that in formal discourse any term other than ‘mutilation’ concedes damagingly to the cultural relativists. ‘FGM’ is therefore the term I use here – though the terms employed may of necessity vary in informal discussion with those who by tradition use alternative vocabulary. See the Feminist Statement on the Naming and Abolition of Female Genital Mutilation, The Bamako Declaration: Female Genital Mutilation Terminology and the debate about Anthr/Apologists on this website.

~ ~ ~

This article concerns approaches to the eradication specifically of FGM. I am also categorically opposed to MGM, but that is not the focus of this particular piece, except if in any specifics as discussed above.

Anyone wishing to offer additional comment on more general considerations around male infant and juvenile genital mutilation is asked please to do so via these relevant dedicated threads.

Discussion of the general issues re M/FGM will not be published unless they are posted on these dedicated pages. Thanks.

The socio-economic dimensions particularly the roles of water, land, knowledge, and wider structural inequalities, shed important light on why FGM persists despite decades of advocacy. I found your framing especially insightful because it connects individual experiences to broader political and economic systems that shape women’s lives.

The concept of a “global backlash” also speaks strongly to realities in settings like Nigeria where gender norms, access to resources, and cultural expectations continue to influence decision-making around FGM. Your work offers a valuable lens for understanding these complexities and for strengthening public health strategies.

Thank you for continuing to open up these difficult but necessary conversations.