Stunted Children: A Global Tragedy. Does FGM Amplify It?

You can TRANSLATE this website to the language of your choice via the Google weblink.

.

Referring to children as ‘stunted’ seems callous, which is probably why this description is rarely employed in general conversation; but in fact the term has a very specific definition and that definition is vitally important.

Referring to children as ‘stunted’ seems callous, which is probably why this description is rarely employed in general conversation; but in fact the term has a very specific definition and that definition is vitally important.

The World Health Organisation says children are defined as stunted if their height-for-age is more than two standard deviations below the WHO Child Growth Standards median.

But does being short matter? Actually, it matters a lot. There is widespread agreement particularly that the ‘first thousand days’ – from conception to age two – are vitally important for all children, wherever they live; and the time after that is also critical. It is difficult, sometimes impossible, to ‘catch up’, if the milestones of childhood are not reached; stunting has impacts for us all.

So this is not about ‘just’ height. Being stunted often serves as a warning that a child’s nutrition is inadequate, and their likely prospects limited. It’s about health, life experiences and expectancy, well-being and capacity to contribute to society. Inevitably, this condition affects many more children in the ‘global south’ than in modern western countries. And, whilst improvements have been noted, the chance that numbers of children with this limitation will occur is increasing globally (perhaps because there are more children now, albeit the percentage rate of occurrence may be dropping), with climate change and other socio-economic impacts becoming greater threats.

Below, we examine some of the influencing factors and likely outcomes for stunted (and other nutritionally disadvantaged) children. Sadly, to date this is not an altogether good news story; it still affects children the world over. And, as I argue below, female genital mutilation (FGM) may be an exacerbating or amplifying factor.

Given that the socio-economic / environmental contexts of FGM and other harms are often multiple, is it time to look more widely, to identify ?causative factor conjunctions where preventative intervention would provide most leverage across the board?

Measurement of stunting

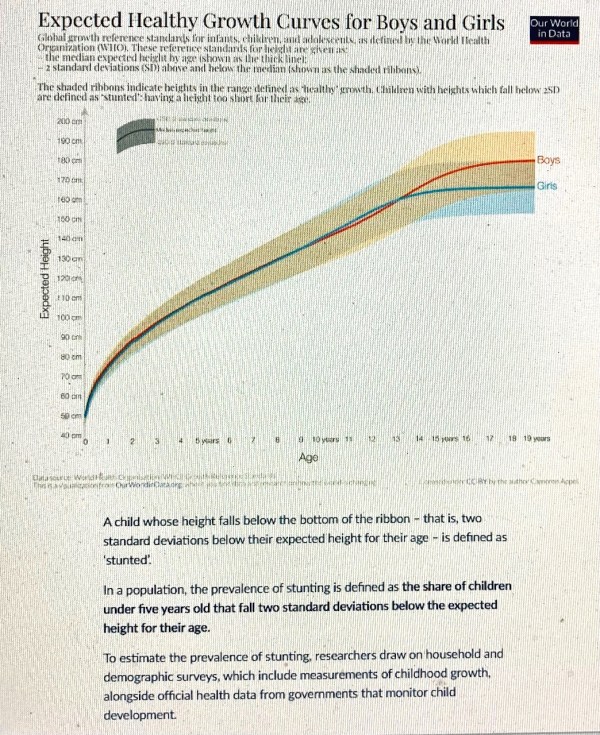

A chart, sourced from the World Health Organisation and designed by Our World in Data, shows how children grow, and at what point / measurement their growth becomes stunted and a matter of concern:

Height is of course not the only measure of being stunted.

This list to the left, also from the World Health Organisation, indicates other indices of stunting. These measures are given for girls and boys separately, broken down by age, initially by weeks and months and later by year groupings.

The indices were first formalised in 2004, and include eg muscle strength as well as variations by country, whilst also providing international standard measurements:

The rationale for developing a new international growth reference derived principally from a Working Group on infant growth established by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 1990. It recommended an approach that described how children should grow rather than describing how children grow; that an international sampling frame be used to highlight the similarity in early childhood growth among diverse ethnic groups; that modern analytical methods be exploited; and that links among anthropometric assessments and functional outcomes be included to the fullest possible extent.

The WHO Working Group also wrote that

Upgrading international growth references to resemble standards more closely will assist in monitoring and attaining a wide variety of international goals related to health and other aspects of social equity. In addition to providing scientifically robust tools, a new reference based on a global sample of children whose health needs are met will provide a useful advocacy tool to health-care providers and others with interests in promoting child health.

These measures are more significant as indicators of the general conditions in which people live, than as cut-offs re risks for individual children. A report in 2020 tells us

…it is helpful to conceptualize stunting as a robust indicator of a deficient environment, which has strong associations with adverse outcomes in the short and long term, rather than the sole cause of poor cognitive development or future risk for chronic diseases.

Stunting has been recognised as a vital issue for decades. Surveys conducted in 57 low- and middle-income countries between 2003 and 2013, involving 129 276 adolescents aged 12–15 years, suggest the prevalence of stunting was then 10.2%. And as of around 2020, an estimated that 149 million younger children, under 5 years of age, some 22%, are stunted worldwide. More than 85% of the world’s stunted children live in Africa and Asia.

It is important to note that the percentage of infants and toddlers who are at risk due to lower than average physical growth varies by country, state and racial/ethnic group, among other factors. This variation also applies to older children growing up in different places, and is ideally reflected in the relative data distribution measurements.

Other frequently nutrition-related child health measures of concern

Wasted children: Wasting is a form of undernutrition that results from a loss of muscle and fat tissue from acute malnutrition. It affects an estimated 45 million children under the age of 5 years (6.8%) worldwide, with more than half of these children living in South Asia. Whilst stunted growth is in some respects the most significant measure, there are further millions of children who are ‘wasted‘ – a measure of weight for height of two or more standard deviations from the median of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards among children under 5 years of age.

Children may be defined as ‘wasted’ if they have a weight-for-length score of –2 or more standard deviations against the WHO reference and ‘stunted’ if they have a length-for-age score of –2 or more. Severe wasting is defined as three standard deviations below the median.

In 2023 nearly half of all deaths in children under 5 were thought attributable to undernutrition; undernutrition puts children at greater risk of dying from common infections, increases the frequency and severity of such infections, and delays recovery.

Failure to thrive: Infants or children who fail to thrive have a height, weight and head circumference that do not match standard growth charts. The person’s weight falls lower than the third percentile (as outlined in standard growth charts) or 20 percent below the ideal weight for their height. This measure may occur early on, or later in childhood where there is an underlying medical or other problem as well as / instead of malnutrition. The many causes of failure to thrive can be complex and are not always fully identified.

Lack of essential nutrients: It is not enough that children have food to eat. They need vitamins, minerals and other trace elements / micronutrients to enable their bodies to grown and develop. This applies to all human beings, but especially to babies and children, if they are to thrive. Deficiencies in any of these requirements may occur in any context, but are particularly critical in locations where other dietary issues also arise.

Overweight and obesity: Other important nutrition-related factors in infant and child health are overweight and obesity. For children under 5 years of age overweight is weight-for-height greater than 2 standard deviations above WHO Child Growth Standards median; and obesity is weight-for-height greater than 3 standard deviations above the WHO Child Growth Standards median. Overweight and obesity are defined as follows for children aged between 5–19 years: overweight is BMI-for-age greater than 1 standard deviation above the WHO Growth Reference median; and obesity is greater than 2 standard deviations above the WHO Growth Reference median.

Since we will not explore aspects of overweight and obesity – an always important issue – more in this piece, we might note here that the World Health Organisation tells us:

About 16% of adults aged 18 years and older worldwide were obese in 2022. The worldwide prevalence of obesity more than doubled between 1990 and 2022.In 2022, an estimated 37 million children under the age of 5 years were overweight. Once considered a high-income country problem, overweight is on the rise in low- and middle-income countries. In Africa, the number of overweight children under 5 years has increased by nearly 23% since 2000. Almost half of the children under 5 years who were overweight or living with obesity in 2022 lived in Asia.

Over 390 million children and adolescents aged 5–19 years were overweight in 2022. The prevalence of overweight (including obesity) among children and adolescents aged 5–19 has risen dramatically from just 8% in 1990 to 20% in 2022. The rise has occurred similarly among both boys and girls: in 2022 19% of girls and 21% of boys were overweight.

While just 2% of children and adolescents aged 5–19 were obese in 1990 (31 million young people), by 2022, 8% of children and adolescents were living with obesity (160 million young people)….. [T]he rise in obesity rates in low-and middle-income countries, including among lower socio-economic groups, is fast globalizing a problem that was once associated only with high-income countries.

Obesity is not the focus of this paper, but it is important that it, like ‘wasting’ and ‘failure to thrive’, is acknowledged as formative in children’s longer term health and well-being / life expectancy.

Maternal anaemia: is another critical factor – a mother who is unwell is less able to (breast)feed her baby and care for it (perhaps a mother who has FGM or similar?). UNICEF tells us that

..low and lower-middle income economies bear the greatest burden of stunting, wasting, low birthweight and anaemia cases.

The UNICEF/WHO/World Bank Joint Child Malnutrition Estimates (stunting, wasting, obesity…) 2020 vs 2022 are available here.

One point to note is that babies and children can be in more than one category, and / or then in none, at various times in their development. The most perilous time period of all is often the first months of life.

Basic causes of stunting – and the intergenerational cycle of disadvantage

Stunting is a process that can affect the development of a child from the early stages of conception until the third or fourth year of life, when the nutrition of the mother and the child are essential determinants of growth (National Library of Medicine / Acta Biomed, 2021). This period of development, particularly from conception to second birthday, is often referred to as the ‘first thousand days‘, and is critical to the child’s future well-being.

The main causes of stunting, as also explained in this video, are

- poor maternal sanitation and health

- inadequate breastfeeding and poor nutrition

- infections.

Infant and child stunting, if not remedied early and adequately, can be associated with negative outcomes throughout life, and even limit life expectancy. These negative outcomes extend however even beyond individual physical health, putting at risk the optimal effectiveness of whole affected communities:

Children whose growth is stunted are more likely to experience higher rates of mortality, morbidity, and suboptimal cognitive and motor development [with long-lasting….] lingering effects of early-life chronic malnutrition. This has serious implications for population health and the fulfilment of the intellectual and economic potential of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Research on the impacts of early stunting explains further why the impacts can be so significant:

This study showed persistent stunting in childhood was associated with lowering of 4–5 IQ points in childhood cognition at 9 years of age. Recovery from early life stunting in children with catch up growth prevented further lowering of cognition scores in these children compared to persistently stunted children. Nutritional supplementation during late infancy and early toddlerhood in addition to continuing nutritional supplementation programmes for preschool and school children can improve childhood stunting and cognitive abilities in vulnerable populations…..

The first 1000 days of life are critical for optimal developmental potential as brain development happens during this period through neurogenesis, neuronal migration, axonal and dendritic growth, synaptogenesis, myelination, and synaptic pruning, and any disruption to this neuronal process can affect long-term structural and functional capacity of the brain. Children exposed to early childhood risk factors thus have not just stunting, but also developmental, cognitive and learning difficulties. Stunting has been identified as a major public health priority due to its association with an individual’s morbidity, mortality, and reduced developmental, learning and economic potential, and its propagation of ‘intergenerational cycle of poverty’.

But a 2017 Save The Children Young Lives report suggests that even delayed interventions for teenage girls, to reduce the impact of stunting, offer hope:

Good nutrition is the key to unlocking every child’s physical and cognitive potential – we must use any and all opportunities to support and sustain good nutrition for children. The window of opportunity in the first 1,000 days after conception is targeted by many nutrition initiatives.

The good news is, there may be a further window of opportunity: adolescence.

Several arguments have been put forward to suggest this is the case. First, nutritional deprivations during adolescence, when growth is rapid, can have dramatic implications for individual health. And second, for girls and women, these deprivations are likely to be transmitted to their offspring, perpetuating the cycle of disadvantage.

Who is ‘stunted’?

A UNICEF report in 2021 tells us that

Globally, 44 percent of infants under 6 months of age were exclusively breastfed in 2019 – up from 37 percent in 2012 but the practice varies considerably among regions. Child malnutrition still persists at an alarming rate –an estimated 149 million children were stunted, 45 million were wasted and 39 million were overweight in 2020. The report presents new projections of potential additional cases of child stunting and wasting due to COVID-19. Based on a conservative scenario, it is projected that an additional 22 million children in low- and middle-income countries will be stunted, an additional 40 million will be wasted between 2020 and 2030 due to the pandemic.

Amongst the key findings of the parallel 2023 report are these:

Global Hunger: While global hunger numbers have stalled between 2021 and 2022, there are many places in the world facing deepening food crises. Over 122 million more people are facing hunger in the world since 2019 due to the pandemic and repeated weather shocks and conflicts, including the war in Ukraine.

Nutritional Access: Approximately 2.4 billion individuals, largely women and residents of rural areas, did not have consistent access to nutritious, safe, and sufficient food in 2022.

Child Malnutrition: Child malnutrition is still alarmingly high. In 2021, 22.3% (148.1 million) children were stunted, 6.8% (45 million) were wasted, and 5.6% (37 million) were overweight.

Why does stunting occur?

As the facts listed above demonstrate, the most obvious cause of stunting and failure to thrive is malnutrition. Safe, nutritious and affordable food is a luxury for many, whether in traditional regions of the global south, or in global north slums and other impoverished locations (such as the often-western commercial ‘food deserts‘ where disadvantaged people cannot access healthy food?). I have explored elsewhere the multiple obstacles faced by many women (particularly those vulnerable to FGM, but also others) to adequate farming and horticultural opportunities, and to this for many millions must be added the absolute poverty and hunger crises, even famine experienced by children and others living precariously at the margins of many societies, ‘developing’ or ‘first world’, across the globe.

And to this must be added the fundamental relevance of knowledge. People who are routinely hungry may well not have the information which would help them to make the best choices even from those somehow available. Illiteracy, or semi-literacy, is a basic limitation on individual agency in such circumstances. As one 2017 study in Liberia has shown, child malnutrition is a direct consequence of ‘abject poverty, food insecurity, illiteracy, the precarious nature of formal and informal work, and the lack of robust social protection’.

But nutritional crises do not simply occur randomly. They happen because of failures of planning, or political neglect, or socio-economic disruption, or inaccessibility, or outright disasters, ‘man’ made or otherwise. Rarely are those most impacted, often women and children, able to resolve the situation unaided, on their own.

Amongst the external factors, beyond basic local food insecurity, which increase the likelihood that a child may be stunted are war / conflict (which may affect older children as much as younger ones), migration (internal and international) / refugee status and climate change (apart from other factors, including rising food prices). Covid has obviously also been a factor across most parts of the world in recent years.

Save the Children makes various connections between stunting and especially climate change very clear:

* Children born in 2020 will face, on average, almost three times as many droughts and crop failures as their grandparents did—with children in low- and middle-income countries continuing to bear the brunt of the climate crisis.

* In Burundi, more than 100,000 people have been forced from their homes due to natural disasters, mostly due to the rise of Lake Tanganyika, Africa’s second-largest lake. Many of these displaced children are only eating one meal a day……

* Madagascar is currently facing its worst drought in four decades, caused by years of failed rains and intensified by a series of sandstorms and locust swarms. One in six children under five is now suffering from acute malnutrition, with numbers rising to one in four children in the six most affected districts.

The issue of climate change is inevitably inter-connected to matters such as conflict and displacement, but it stands alone in respect of potential stunting as the factor, regardless of politics, which every one of us as more privileged individuals can to a tiny degree influence.

Why is FGM not a noted factor in stunting?

There are however matters which must affect stunting which seem not to have been generally acknowledged. Given that female genital mutilation (FGM) is a fact of lived experience for well over two hundred million (yes, about 240,000,000) women and girls alive today, this must surely be one of the factors which influences stunting? FGM can be fatal, and is often incapacitating, as was reported following research in a number of African countries published back in 2006:

Women with any degree of FGM also had a 15-55% increased risk of stillbirth or early neonatal death – with more extensive FGM causing the highest risk – compared with women who had not had the procedure.

Their babies were also more likely to die during labour. [Emily] Banks [lead researcher] observed one to two extra deaths per 100 deliveries of babies born to mothers with FGM, against a background risk of 4-6 deaths per 100 deliveries.

Research has shown that FGM increases maternal ill-health, and sometimes causes death. A report (2023) in Nature tells us that

… estimates imply that a 50% increase in the number of girls subject to FGM increases their 5-year mortality rate by 0.075 percentage point [which] translates into an estimated 44,320 excess deaths per year across countries where FGM is practised. These estimates imply that FGM is a leading cause of the death of girls and young women in those countries where it is practised accounting for more deaths than any cause other than Enteric Infections, Respiratory Infections, or Malaria.

Likewise, maternal FGM increases infant morbidity and mortality, as this study (2013) in The Gambia shows: babies are more at risk during delivery if the mother has had any form of FGM:

Complications during delivery … have serious repercussions for the health of the newborn. Fetal distress was more commonly observed in the babies of women with type I or II FGM/C, confirming the fact that prolonged labor as a result of FGM/C affects the health of the newborn, as reflected in the stillbirth rates.

This finding is replicated at a global level by a WHO briefing paper in 2024 which states that

Obstetric complications can result in a higher incidence of infant resuscitation at delivery and intrapartum stillbirth and neonatal death…

A consequence of such complications, however caused, was noted in eg Bangladesh and Tanzania decades back, and can translate into tragedy for both mother and child:

….[Bangladeshi] children whose mothers died were much more likely to die than those whose fathers died, and both groups had higher mortality than children whose households did not experience an adult death. Most deaths were among children under 1 year old. After the first month of life, female children were much more likely than male children to die…..

The results from random-effects and fixed-effects regression models showed that [Tanzanian] children who lost their mothers were much more likely to be stunted than children who lost their fathers or than children with both parents living.

Whilst, as this 2023 report indicates, there is still much to be learnt about the impact specifically of maternal FGM on babies and children, we still don’t know in any detail to what extent maternal death or illness, particularly as a result of FGM in traditional settings, affects the life outcomes of their babies:

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates the aggregate cost of medical treatment for girls and women after FGM was $1.4 billion in 2018. However, until now, there has been no systematic evidence about the role of FGM in the global epidemiology of child mortality – reflecting difficulties in measuring the practice.

Is it not strange that, with a directly relevant population of well over two hundred million affected women and girls, still not much is known about the health prospects over time for children whose mothers have FGM? – even though studies (including this one) suggest that stunting is an intergenerational health problem, passing from mother to child. As this 2019 report on the Intergenerational Effects of Stunting on Human Capital says:

The [Indian] National Family Health Survey (NFHS) 2015-16, reveals that among the total number of stunted children under five, 51 percent has no education. Also, more than half of the stunted children under five belong to the lowest wealth quintile. This gives rise to two major implications. First, stunting negatively affects the level of education, thus reducing human capital. Second, since more than a half of stunted children under five belong to the lowest wealth quintile, it implies that one of the factors affecting stunting is the socio-economic status of the household.

UNICEF (2013), in its report “Improving Child Nutrition: The achievable imperative for global progress”, has provided a conceptual framework of malnutrition, which captures the intergenerational consequences and the immediate, underlying and basic causes of malnutrition. It can be demonstrated that over and above the immediate and underlying causes of malnutrition, there exist three basic causes including household access to adequate quantity and quality of resources, inadequate financial, human, physical and social capital and the socio-cultural, economic and political context that heavily influence maternal and child undernutrition…

As we remarked above, stunting is not something which occurs out of the blue. It is fundamentally connected within the contexts in which people live.

Global south and global north, too (a digression to the UK)

Perhaps a quick digression to consider one of the wealthiest countries on our planet illustrates the enormity of the challenge we face in abolishing child stunting everywhere.

This issue is not ‘only’ about children born in ‘developing’ locations. To our shame, stunting seems also to be impacting the so-called ‘first world’, at least in my own nation, the UK.

There cannot be any excuse for this headline in July 2022: Alarmingly poor nutrition causing stunting across UK, Food Foundation report reveals, or this in June 2023: Children raised under UK austerity shorter than European peers, study finds.

Nor is it reassuring to learn, if we seek information about the Sustainable Development Goals Indicator 2.2.1 – Prevalence of stunting (height for age <-2 standard deviation from the median of the World Health Organization (WHO) Child Growth Standards) among children under 5 years of age, that since September 2023 the UK Government has

…. paused the uploading of data reported on this site [Sustainable Development Goals – sdgdata.gov.uk].

However, the hyperlinks for the indicator data sources could be used to see where the data is published and whether newer data will become available in future. You can also find up to date SDG data on the UN SDG website which reports globally comparable data.

The Food Foundation’s July 2022 publication, The Broken Plate, explains that

… we urgently need government action to deal with the crisis affecting the entire food system. The overwhelming problems are poverty combined with the sale and promotion of cheap unhealthy food.

Poor nutrition is causing stunted growth. British five-year-olds are shorter than five-year-old populations of our European neighbors, and there is significant height variation between poor and wealthy areas across the UK.

So what factors may be at play in the UK’s increase in infant and child stunting?

It is very difficult to untangle the (anyway inadequate) data, but perhaps these factors are relevant?

We know in the UK that BAME (Black and minority ethnic) women and their babies are more at risk than others during pregnancy, birth and in the post-delivery period.

We know that Black children particularly are disadvantaged, developmentally ‘behind’ most others by the time of their early years assessments (age 4-5) – a situation made worse for BAME children by the Covid epidemic in the years around 2022.

We also know that migrant / refugee children coming to the UK (many originally from sub-Saharan Africa) are at particular risk of failures of care provision, including nutrition and health:

Reports from outreach organizations and academic centres reveal a large gap in information about how refugees and asylum-seekers obtain and prepare food for young children in the UK…. There are no general public health models with which to predict for any age group the health implications of dietary and lifestyle changes after arrival or during settlement. The complex emergencies that produce refugees commonly create conditions for disease transmission and nutritional vulnerability, and the general process of becoming a refugee commonly induces maladies such as post-traumatic stress syndrome, many of which affect children….

In Britain, refugees constitute one of the most socially excluded groups in society, and are seldom included in health interventions. Like many other migrants to the UK, refugees typically settle in the poorest districts of large cities where, as `ethnic minorities’, they encounter multiple deprivations including limited access to work, welfare and healthcare…

In Europe, newly resettled children have been found more likely to display chronic medical conditions, caries and obesity than poor growth status35 ; however, large US samples have identified substantial proportions with low birthweight, nutritional stunting and deficiencies of vitamin A and iron that decrease over time and are related to nutritional and health factors rather than genetics.

And we know that in the UK, as elsewhere, some of these BAME and refugee children will have been born to women with FGM.

I do not doubt that stark poverty and neglect – matters we could all choose to address much, much better – account for much child stunting and ensuing adult misery everywhere in the world, but I remain also convinced that FGM, the experience of literally hundreds of millions of women and girls alive today, is also a factor in the intergenerational misfortune of many children, girls and boys alike.

Some questions

There must surely be people somewhere looking at how FGM and other violence against women and girls affects child stunting (and at how stunting then self-replicates). It is impossible that no-one has actually considered this. But whatever the work done so far, it has not reached the positioning and policies of those with the ultimate power to decide what to do about these grim matters.

It is vitally important that greater efforts are made to join the dots.

I have previously argued that water is a critical issue for the eradication of FGM, both in the burden it imposes on the 200 million hours every day that (mostly) women must spend collecting it, and in regard to the issues such as agriculture / food and WASH (water, sanitation and hygiene).

But policy-makers, mostly men, can improve access to clean water and change the contexts which have enabled FGM, to everyone’s advantage; and there are also many other environmental and low-tech ways in which the status of women in different parts of the world might be improved – this latter being an essential part of the general strategy needed to bolster the health and well-being of everyone, including many millions of women and their children.

FGM is a much bigger cost to any economy that ‘simply’ (albeit critically) the cost to those on / by whom it is imposed. We know too that stunting is economically costly and life limiting. Perhaps it is time to develop an overt Economic Index for stunting such as I have already proposed for FGM.

Stunting is a socially preventable tragedy. So is FGM. There must surely also be a pernicious, negative synergy when, sometimes inevitably, these two damaging conditions combine. Is it not likely that when these two issues coalesce, they mutually amplify social and human costs, and that diminished life experience and community disfunction are the outcome?

The tragedies of many disadvantaged people’s lives, more often the experiences of women and children in their millions, cannot adequately be addressed in silos.

Water, nutrition, stunting and many other issues are all interconnected.

Our job now is to find out in what ways these factors interplay, so that we, those of us who seek a better world for women and children, can more effectively work towards that end. Yet again, the mantra must be ‘only connect….’. Piecemeal approaches to specific, individual issues will only take us so far.

We know stunting is a massive obstacle to children reaching their potential; it can harm whole economies via its cruel impact on individuals. And we know that harmful practices such as FGM can also have pernicious impacts at individual, community and socio-economic levels. So is there negative synergy when these two collide?

What more needs to be done generally, and location-specifically, to mitigate any such consequences?

Why is so little attention paid in mainstream political discourse, whether in the global south or the global north, to phenomena like stunting? Why has FGM, similarly such a devastating fact of life for so many, now again become an issue of so little interest? Why are we, it seems, so reluctant to explore the bases of these cruel afflictions, which lie within the unspoken ‘culture’ of patriarchy incarnate – the damaging imposition via war, harmful practices, hunger, denied resources, etc, of powerful men’s will on the minds and bodies of, particularly, women and girls.

Is it not convenient that stunting, water (health and hygiene), FGM and the like are generally avoided in polite conversation?

Why are the full economic and social costs of these phenomena and their synergies not ruthlessly exposed? If we knew more about the amplified costs of such synergies perhaps we would know better which aspects need our most urgent attention?

That avoidance – don’t talk about ‘rude’ matters – serves the interests of some powerful people, but it does not serve either affected individuals or society at large.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

This post relates to the four posts here I wrote in February and March 2024, looking at the way my perceptions around the contexts of eradicating FGM have changed (hopefully, developed?) over the past decade:

Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation: Identifying Tensions And Challenges (February 6 – International Day of Zero Toleration for FGM)

Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation: Looking At Practical And Low-Tech Ways Forward (March 8 – International Women’s Day)

Men As Policy-Makers Must Support #EndFGM – Enable Women To Gain Respect As Adults Via Fair Social And Economic Contexts (14 March – Commission on the Status of Women, CSW68)

World Water Day – And Why It Matters For #EndFGM (March 22 – World Water Day)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Read more about FGM and Economics

Your Comments on this topic are welcome.

Please post them in the Reply box which follows these announcements…..

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Books by Hilary Burrage on female genital mutilation

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6684-2740

Hilary has published widely and has contributed two chapters to Routledge International Handbooks:

Female Genital Mutilation and Genital Surgeries: Chapter 33,

in Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health (2019),

eds Jane M. Ussher, Joan C. Chrisler, Janette Perz

and

FGM Studies: Economics, Public Health, and Societal Well-Being: Chapter 12,

in The Routledge International Handbook on Harmful Cultural Practices (2023),

eds Maria Jaschok, U. H. Ruhina Jesmin, Tobe Levin von Gleichen, Comfort Momoh

~ ~ ~

PLEASE NOTE:

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, which has a primary focus on FGM, is clear that in formal discourse any term other than ‘mutilation’ concedes damagingly to the cultural relativists. ‘FGM’ is therefore the term I use here – though the terms employed may of necessity vary in informal discussion with those who by tradition use alternative vocabulary. See the Feminist Statement on the Naming and Abolition of Female Genital Mutilation, The Bamako Declaration: Female Genital Mutilation Terminology and the debate about Anthr/Apologists on this website.

~ ~ ~

This article concerns approaches to the eradication specifically of FGM. I am also categorically opposed to MGM, but that is not the focus of this particular piece, except if in any specifics as discussed above.

Anyone wishing to offer additional comment on more general considerations around male infant and juvenile genital mutilation is asked please to do so via these relevant dedicated threads.

Discussion of the general issues re M/FGM will not be published unless they are posted on these dedicated pages. Thanks.