22 March is World Water Day, a date the UN first observed in 1993. Attention is focused on the global water crisis, highlighting the 2.2 billion people living without access to safe water. The 2024 theme, Leveraging Water for Peace, shines a light on action to tackle the devastation of global water and sanitation failures, not least for women and girls. This failure to provide safe water for consumption and hygiene is both a general crisis and one, I suggest, relating specifically to FGM (female genital mutilation). What follows are some reasons why.

You can TRANSLATE this website to the language of your choice via Google Translate.

UNICEF says women and girls spend 200 million hours every day collecting water.

“200 million hours is 8.3 million days, or over 22,800 years,” said UNICEF’s global head of water, sanitation and hygiene Sanjay Wijesekera. “It would be as if a woman started with her empty bucket in the Stone Age and didn’t arrive home with water until 2016. Think how much the world has advanced in that time. Think how much women could have achieved in that time.”

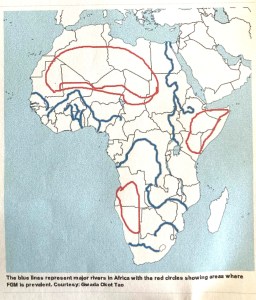

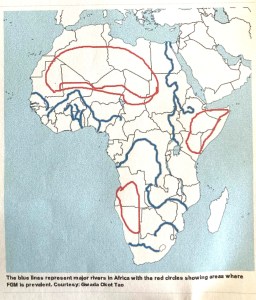

This observation throws into sharp relief why we need here first to consider how and why water is such a critical issue in many parts of the ‘developing’ world / ‘global south’. Thereafter we will also ask how the adequate availability of clean water might influence efforts to end FGM – unfortunately a matter rarely at the forefront of water policy. This map by Ugandan Gwada Okot Tao helps to illustrate why water may be so important:

Water, we learn via the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 6),

.. is essential not only to health, but also to poverty reduction, food security, peace and human rights, ecosystems and education:

Access to safe water, sanitation and hygiene is the most basic human need for health and well-being. Billions of people will lack access to these basic services in 2030 unless progress quadruples. Demand for water is rising owing to rapid population growth, urbanization and increasing water needs from agriculture, industry, and energy sectors.

The demand for water has outpaced population growth, and half the world’s population is already experiencing severe water scarcity at least one month a year. Water scarcity is projected to increase with the rise of global temperatures as a result of climate change.

Investments in infrastructure and sanitation facilities; protection and restoration of water- related ecosystems; and hygiene education are among the steps necessary to ensure universal access to safe and affordable drinking water for all by 2030….

In 2022, 2.2 billion people still lacked safely managed drinking water, including 703 million without a basic water service; 3.5 billion people lacked safely managed sanitation, including 1.5 billion without basic sanitation services; and 2 billion lacked a basic handwashing facility, including 653 million with no handwashing facility at all.

The failure to provide adequate hygiene facilities is dangerous for everyone, but, as UNICEF tells us, especially for babies and small children:

Collection of water can affect the health of the whole family, and particularly of children. When water is not available at home, even if it is collected from a safe source, the fact that it has to be transported and stored increases the risk that it is faecally contaminated by the time it is drunk.

This in turn increases the risk of diarrhoeal disease, which is the fourth leading cause of death among children under 5, and a leading cause of chronic malnutrition, or stunting, which affects 159 million children worldwide. More than 300,000 children under 5 die annually from diarrhoeal diseases due to poor sanitation, poor hygiene, or unsafe drinking water – over 800 per day.

‘Stunted’ children – those who have failed to reach their growth potential as a result of disease, poor health and malnutrition – are likely to suffer suboptimal physical and cognitive development, impacts that can persist throughout their lives (and which obviously add to the concerns of their mothers and families).

These basic facts about why water is fundamentally critical to life are spelt out further in the SDG6 (‘Ensure access to water and sanitation to all’):

…. Without better infrastructure and management, millions of people will continue to die every year from water-related diseases such as malaria and diarrhoea, and there will be further losses in biodiversity and ecosystem resilience, undermining prosperity and efforts towards [more sustainability].

Civil society organizations should work to keep governments accountable, invest in water research and development, and promote the inclusion of women, youth and indigenous communities in water resources governance.

This need for workable liaison between all the various partners in developments around water policy and provision can only become more compelling as the inevitable impacts of climate change and other environmental challenges become more evident. The inclusion of women – 50% of the workforce in Africa – as policies are developed is vital. In the words of a Farming systems & Climate change Senior Scientist at the Alliance of Bioversity International:

When women are co-designers of irrigation technologies and equal partners in implementing solutions, the location, purpose and scale of projects are optimized to women’s rights and needs, benefiting everyone.

Increased frequency and severity of heat waves, rain and drought will continue to constrain Africa’s water resources. Competition for water among user groups, such as farmers and pastoralists, or between communities in upper and lower zones, could lead to social instability or even civil conflict. With women contributing to solutions, we could avert these undesirable outcomes and achieve water security.

Water criticality impacts on women

The criticality of involvement in water availability by women, including those in indigenous communities, is clear. Further evidence gives some reasons why:

As we saw above, women and girls (mostly in the sub-Saharan region and other parts of the so-called global south) spend 200 million hours every day collecting and carrying water. UNICEF rightly opines that this is a ‘colossal waste of time‘, largely a waste which falls mightily on the shoulders of women and girls:

When water is not piped to the home the burden of fetching it falls disproportionately on women and children, especially girls. A study of 24 sub-Saharan countries revealed that when the collection time is more than 30 minutes, an estimated 3.36 million children and 13.54 million adult females were responsible for water collection. In Malawi, the UN estimates that women who collected water spent 54 minutes on average, while men spent only 6 minutes. In Guinea and the United Republic of Tanzania average collection times for women were 20 minutes, double that of men.

And so the essential case for the provision of safe and accessible water for women and girls is made. Women lose many hours which they would otherwise spend on small-holdings or at work elsewhere, and girls (like some boys) miss school. The burden of water collection also means women and girls are subjected to sometimes dangerous journeys, with the risk of pain and exhaustion and damage to their physical and mental health, and perhaps even to assault enroute (or because they ‘fail’ to provide domestic services due to water collection duties).

This Global Policy observation in 2012 about water and similar inadequate policies affecting women more than men probably remains largely valid. Policy in water, agriculture and food management continues to be made mostly by men.

While women do most of the farm work, their role in decisions related to water, agriculture and food management is very limited. Women have held a restricted number of positions in government ministries dealing with agriculture and natural resources. Most African states are parties to international conventions protecting rights of women, and even have national laws that prevent gender based discrimination; however there is a clearly perceived gap between policy and implementation.

The complexities of how land and water issues impact on women are many. Whilst beyond the scope of this discussion around specific aspects of water availability, these reports: Women Smallholder Farmers: What is the Missing Link for the Food System in Africa?, and Women grow 70% of Africa’s food. But have few rights over the land they tend offer important insights into both water and other challenges / obstacles mostly faced by women farmers on that continent.

More alarming still is this report from India about women who have chosen / felt obliged to be sterilized because of disruptions to their lives brought about by climate change.

Hygiene, menstruation, childbirth and FGM

Self-evidently the basic biological facts of hygiene, menstruation, often childbirth and, where relevant, FGM are matters which impinge directly on the lives of all female human beings. Readers who claim a delicate disposition should look away now, there is no anodyne way to consider these fundamental aspects of women’s experience; but they matter.

Firstly, women and girls have different personal hygiene requirements than boys and men. Of course everyone needs to wash and keep clean, but things are more complicated for women, not least when they menstruate. For some, period poverty – being unable to afford (or perhaps even find) menstrual protection – is a real problem, much compounded when there is nowhere to seek privacy, or even safe water, for changing and washing.

The reluctance in some places to acknowledge or discuss menstruation, or to explain it to girls and boys alike as a natural part of life, is lessening, but the practical issues – taboos, myths, lack of facilities, no means to manage the flow – can remain. UN Women reckons that 1.25 billion women and girls worldwide have no safe, private toilet to which they can go. Proper arrangements in schools can, but still may not, ensure that girls have these necessary facilities.

The need for clean running water is even greater in relation to maternity. As WaterAid explains, risks of infection are high, for both mother and child:

The world is experiencing a maternal health crisis, but those of us living in countries where clean water, decent toilets and good hygiene are often taken for granted may not be aware of it. The crisis is taking place in developing nations all over the world, where access to water, toilets and hygiene present many challenges despite being a basic human right. Currently, almost one in two people worldwide are using healthcare facilities with nowhere to safely wash their hands, and 765 million people are using healthcare facilities with no toilets at all.

Under these circumstances, it doesn’t matter how much training healthcare workers have, how many hours they work, or how much they care about their patients. It is near impossible for them to protect their own health and provide safe maternity care without the basics they need, including clean water and soap. Without them, pregnancy and childbirth become deadly. Infections associated with unclean births currently account for over a quarter of newborn deaths and 11% of maternal mortality each year – together accounting for more than 1 million deaths annually.

All these issues, already very serious, are compounded if a woman or girl has had female genital mutilation (FGM). Yet the literature on water and health, even the recent evaluation of gender and progress on the SDG6 targets for universal access to safe drinking water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH), seem rarely, if ever?, to mention FGM, a critical feature of the experience of at least two hundred million human females.

The impacts and longer-term consequences of FGM are well documented by the WHO and others:

Long-term consequences of FGM can include:

- urinary problems (painful urination, urinary tract infections);

- vaginal problems (discharge, itching, bacterial vaginosis and other infections);

- menstrual problems (painful menstruations, difficulty in passing menstrual blood, etc.);

- scar tissue and keloid;

- sexual problems (pain during intercourse, decreased satisfaction, etc.);

- increased risk of childbirth complications (difficult delivery, excessive bleeding, caesarean section, need to resuscitate the baby, etc.) and newborn deaths;

- need for later surgeries: for example, the FGM procedure that seals or narrows a vaginal opening (type 3) needs to be cut open later to allow for sexual intercourse and childbirth (deinfibulation). Sometimes genital tissue is stitched again several times, including after childbirth, hence the woman goes through repeated opening and closing procedures, further increasing both immediate and long-term risks;

- psychological problems (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, low self-esteem, etc.).

It is blatantly obvious that all these injuries will be exacerbated by failures to provide the basic requirements – of which clean water is the most fundamental – for personal hygiene. But research on the dire need for fresh water in all communities ignores FGM.

FGM and the water crisis

Is there any research on how and to what extent FGM amplifies the already serious consequences of the water crisis?

> Women and girls with FGM are probably at even more risk of illness or death from no clean water than other women

One organisation at least, Amref: health africa, does address both water and FGM; but its commentary suggests they are seen as largely complementary or separate matters:

Water and rights: Spending less time and effort to access water means that women and girls are able to attend school, engage in income-generating activities, and improve their health and well-being. They’re also able to engage with the programme to end harmful cultural practices such as FGM/C and early marriage.

This dual approach of WASH – [water, sanitation and hygiene] building sustainable safe water supplies, improving infection prevention and control – and ARP [alternative rites of passage*]– reducing cases of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C), early marriage, and teenage pregnancy – creates a powerful tool to increase acceptance and support for the community-led ARP model by cultural and political leaders. The programme is generating evidence, sharing lessons learnt, and best practices for ending FGM/C, early marriage, and teenage pregnancy through this approach.

[*Alternative Rites of Passage: community ‘coming of age’ ceremonies in which the girl is celebrated but FGM is not imposed – a strategy with varying degrees of success in different locations.]

Nonetheless, the likely impacts on those with FGM of failures to deliver clean water to communities seems not to be noted. Where are the studies which would clarify whether millions of women and girls with FGM (and their babies) are especially vulnerable in such circumstances? One might at least expect healthcare professionals (who are increasingly involved in ‘medicalized‘ FGM and may be open to persuasion to stop doing it) would understand and speak out on this matter.

Whilst ‘the science’ (health impact evidence) may not always change minds about FGM, it is known that to a degree, for some people, it will do so.

It is perhaps cruelly ironic, as ActionAid tells us, that in some communities only girls and women who have been ‘cut’ – those whose health may be most affected – are permitted to handle food or collect water:

In many communities, FGM is considered an important rite of passage into womanhood: girls may be outcast socially if they refuse, including being unable to marry.

In some communities in Uganda, a woman who hasn’t undergone FGM is not allowed to get food from the store, collect water, or even speak in public. In order to avoid FGM, she may have to escape from her family and community.

QUESTION 1: Given the surely high probability that even basic hygiene facilities are not available to some women and girls with FGM – how many, we don’t know – why has this not been incorporated into research and policies around water provision?

> Possible connection between water availability and incidence of FGM

In June 2014 ReliefWeb published an intriguing news report entitled Improved Access to Water May Hold the Solution to Ending FGM in Africa. The new item concerned a discovery made by Gwada Okot Tao, a ‘female genital mutilation (FGM) traditional surgeon’ commissioned by a local consortium, the Citizens’ Coalition for Electoral Democracy in Uganda (CCEDU), that sought to answer governance issues among communities that circumcise and those that don’t. (In Kenya, communities that circumcise believe that those that don’t are not capable of leading and this had raised governance issues.) Gwada admits he made the discovery by accident:

KAMPALA, Jun 20 2014 (IPS) – Could it be possible that if women in Africa had access to water, it could save them from undergoing the harmful practice of female genital mutilation (FGM)? It seems that according to yet-to-be released research by Ugandan Gwada Okot Tao, FGM and other forms of circumcision in Africa could be linked to water.

Gwada, who conducted research among 20 ethnic groups across Africa, including Kenya, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Uganda, Ghana, and South Africa, says that ethnic communities that practice FGM in Africa can be found in areas where the water supply is problematic.

Gwada found that in Kenya, for example, only three of the East African nation’s 63 ethnic groups did not practice any form of circumcision. And these three communities were found in the Rift Valley region, where there are water bodies like lakes and rivers.

He believes that FGM has become a prevalent cultural practice as a consequence of a lack of water.

… “Every thing is wrong, the policies are wrong, legislation is wrong because they were not informed by what made the communities start the practice in the first place,” Gwada tells IPS.

… Caroline Sekyewa the programme coordinator of DanChurchAid, says the research finding is convincing because in the communities that practice FGM, a girl who has gone through the ritual is regarded as “clean”… “It may not necessarily mean that the provision of water is the solution to FGM, largely because culture has hijacked the practice, but the this could inform the intervention strategies towards its elimination.”

Gwada’s research has not, it seems, since been made fully public – or perhaps it has, though difficult to find on the internet? – but it was shared with selected stake holders. Importantly however Sekyewa added that her organisation would also target policy makers to provide water in the affected areas.

In Pokot, a region where FGM is rampant, women walk several kilometres to fetch water and the situation is complicated with insecurity caused by armed cattle rustlers. An underground water aquifer was discovered in the Turkana region on the other side of Kenya, which borders the Pokot. Sekyewa says such a water resource, shared by the border communities, could solve the problem. (Whether it did or not is from accessible reports unclear; but certainly in general hydrologists can help to find answers. Water resources in Africa are as yet sparsely explored. There is work to be done.)

This brief report of a finding about FGM and water, cited here at some length because it seems to stand alone, cannot of itself change significant policies, but it leads to significant questions:

QUESTION 2: Are there locations where structural failures of access to water have influenced a decision that women and girls should undergo FGM to stay ‘clean’? Are there any related factors which may come into play?

And have any other, perhaps more substantial, surveys been conducted to see if the proximity of clean water is a factor in some communities’ adoption or otherwise of FGM?

> Denial of resource control (water, land) is a denial of women’s autonomy and adult status

Nothing about FGM applies to all versions of its rationales, but in some locales one ‘reason’ is that it makes a girl a ‘woman’, then able to marry (NB sometimes as one of two or more wives) and conduct herself as an adult.

I have however suggested elsewhere that the incidence of FGM in a community may be reduced if women are accorded adult status for other ‘reasons’ than being cut.

One such possibly viable reason is that the woman has command of resources such as land and water. Yet, as we saw above, barely any women in traditional communities have such control as of right. They may well till the land and fetch the water and look after the children and feed the family and so on. The economic value is substantial (with estimates ranging from 10 to 60 percent of GDP); but their labour counts for little, and their legal rights to these resources are often non-existent.

This non-status and failure to acknowledge women’s economic worth is critical; and one means by which it might be addressed is via sex-disaggregated data.

Consider these commentaries (emphases mine):

Status of sex-disaggregated data in the UN system

One of the key stumbling blocks to achieving a more robust gender-integrated international policy regime is the astonishing lack of comparable international data on gender-sensitive water indicators. International policy mechanisms are driven first and foremost by data. Without sex-disaggregated data, it is not possible to fully measure progress towards Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Without data, it is difficult to make effective analytical assessments of the comparative situation of women and men in different communities or parts of the world (UN DESA, 2009). If data are not available on a topic, no informed policy will be formulated; if a topic is not evident in standardized databases, then, in a self-fulfilling cycle, it is assumed to be unimportant.

…

Where are the women? Filling the gap in sex-disaggregated data in agriculture

… with more than two-thirds of the population in low-income countries working in agriculture, the failure to collect data that captures women’s voices and reveals gender-differentiated nuances in agriculture means missing out on an enormous piece of the labor and productivity picture and ultimately, on the full reality of life and progress in these countries…

One way to fill these gaps is through the instruments we use to collect the data. To start, agricultural and rural surveys need to cover gender issues. The 50×2030 Initiative survey tools are designed to capture gender-relevant information with differing degrees of gender-disaggregated information.

…

Economic and rural development through gender-responsive water-management policies

The [South African] government and other stakeholders need to prioritise community-based initiatives, capacity-building programmes and awareness campaigns, and emphasise collecting disaggregated data on water usage and access. These projects should aim at enhancing women’s knowledge, participation and decision-making in water-related activities to help close gender inequality and water-access gaps.

… [while the] government has taken steps to address historical injustices and gendered disparities in water access, challenges persist. “Comprehensive reforms in land-water governance, effective implementation of existing laws and targeted strategies to empower women – including through education – are crucial for rectifying the gendered nature of water access in post-apartheid South Africa.”

Perhaps the vital insights which sex-disaggregated data can provide are best recognised in this quote from Monique Nsanzabaganwa of the National Bank of Rwanda:

“You have all [the sex-disaggregated data] you need to make yourself feel uncomfortable. Statistics are very, very powerful.“

Measuring Women’s Financial Inclusion: The Value of Sex-Disaggregated Data

If women’s economic contributions are not recognised, they lack status. If they lack status they are without autonomy and obliged to seek it through marriage and other family ties.

If however women have actual rights to their own resources and genuine engagement in the economic and structural aspects of their communities, they are more likely to seek education, be seen as self-determining and able to conduct their lives as independent adults.

QUESTION 3: Is legal autonomy – e.g. independent rights as an adult to determine how to develop and use resources such as land and water – one step towards the eradication of FGM?

And is actual access to water, vastly diminishing the 200 million hours every day currently taken by water collection, one aspect for some towards gaining adult status without FGM?

Male perspectives alone don’t work

Female genital mutilation is the ultimate in enduring patriarchy incarnate. It will be difficult to eradicate fully any time soon.

Nonetheless over time I have explored many aspects of FGM and the economic factors which sometimes underlie it. I have even suggested An Economic Deficit Index for FGM? Human Capital, Sustainable Development And Land, drawing on the World Bank’s Human Capital Index, and considering matters such as maternal well-being and numbers of ‘stunted’ children in a country. Water is another compelling aspect of these equations; we neglect the physical world and environment at our – and especially women’s – peril.

As things stand however I can’t even answer my own questions as above, but I hope before long we will know more about these issues. Perhaps this ‘Launch version’ WHO / UNICEF report:

Progress on household drinking water, sanitation and hygiene 2000–2022: special focus on gender is a start?

.

Water and FGM are both, in their conflicting ways, matters of life and death. If we want to end FGM, it’s time we started thinking about how these intertwined and fundamental aspects of far too many women’s experience may correlate.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

This post is the final one of four posts here which I have written in February and March 2024, looking at the way my perceptions around eradicating FGM have changed (hopefully, developed?) over the past decade:

Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation: Identifying Tensions And Challenges (February 6 – International Day of Zero Toleration for FGM)

Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation: Looking At Practical And Low-Tech Ways Forward (March 8 – International Women’s Day)

Men As Policy-Makers Must Support #EndFGM – Enable Women To Gain Respect As Adults Via Fair Social And Economic Contexts (14 March – Commission on the Status of Women, CSW68)

World Water Day – And Why It Matters For #EndFGM (March 22 – World Water Day)

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

This post was distributed on 18 April 2024 via the Women’s United Nations Report Network (WUNRN). It has also been shared with the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), with reference to the forthcoming Water on the Frontlines for Peace 2024 Triennial Congress (May 30 – June 2), and with the US Women’s Caucus for UN Advocacy.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Appendix, October 2025

This new report from Iran illustrates very clearly the simple fact that water is a fundamentally feminist issue:

The Gendered Dimensions of the Water Crisis in Iran: Impacts on Women’s Health, Livelihoods, and Security

Water will likely soon become the prime contested resource on which the well-being of women – and children, and men, and our planet – depends.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Read more about FGM and Economics and FGM and Environment

Your Comments on this topic are welcome.

Please post them in the Reply box which follows these announcements…..

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Books by Hilary Burrage on female genital mutilation

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6684-2740

Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation: A UK Perspective

Ashgate / Routledge (2015) Reviews

Hilary has published widely and has contributed two chapters to Routledge International Handbooks:

Female Genital Mutilation and Genital Surgeries: Chapter 33,

in Routledge International Handbook of Women’s Sexual and Reproductive Health (2019),

eds Jane M. Ussher, Joan C. Chrisler, Janette Perz

and

FGM Studies: Economics, Public Health, and Societal Well-Being: Chapter 12,

in The Routledge International Handbook on Harmful Cultural Practices (2023),

eds Maria Jaschok, U. H. Ruhina Jesmin, Tobe Levin von Gleichen, Comfort Momoh

~ ~ ~

PLEASE NOTE:

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, which has a primary focus on FGM, is clear that in formal discourse any term other than ‘mutilation’ concedes damagingly to the cultural relativists. ‘FGM’ is therefore the term I use here – though the terms employed may of necessity vary in informal discussion with those who by tradition use alternative vocabulary. See the Feminist Statement on the Naming and Abolition of Female Genital Mutilation, The Bamako Declaration: Female Genital Mutilation Terminology and the debate about Anthr/Apologists on this website.

~ ~ ~

This article concerns approaches to the eradication specifically of FGM. I am also categorically opposed to MGM, but that is not the focus of this particular piece, except if in any specifics as discussed above.

Anyone wishing to offer additional comment on more general considerations around male infant and juvenile genital mutilation is asked please to do so via these relevant dedicated threads.

Discussion of the general issues re M/FGM will not be published unless they are posted on these dedicated pages. Thanks.

Well done, Hilary! It’s becoming increasingly important to link FGM to so many issues that may not appear of immediate relevance but that can indeed help untie strands of complexity that envelope the issue. In light of retrograde politics and the undoing of feminist progress worldwide, the urgency of this expanded examination intensifies. Case in point: the Gambia …